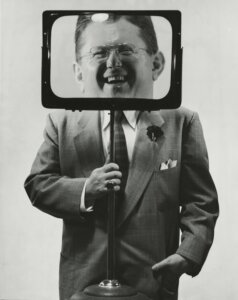

Don Rickles, 1980. Photo by Getty Images

The recent uproar over right-wing comedian Tony Hinchcliffe’s racist and sexist jokes at Donald Trump‘s Madison Square Garden rally may cost the Republican party some votes, according to political pundits. Insults directed at Jews, Palestinians, Blacks and Latinos were justified by Hinchcliffe who posted on his social media a clip of the Jewish insult comedian Don Rickles at an event celebrating Ronald Reagan.

The Jewish comedian Harry Shearer tweeted in response that Tony Hinchcliffe “is no Don Rickles.” Beyond this self-evident assertion, there is the recurrent impression that the American electoral arena has declined into a mix of children’s playground and professional wrestling ring where unrestrained jibes and invective replace anything approaching wit.

Forgetting or misinterpreting the legacy of supreme Jewish insult comedians like Jack E. Leonard, Rickles, Joan Rivers and others may be part of the problem.

The comedy roast was essentially a Jewish creation, invented well before the heyday of Don Rickles and his contemporaries. This Jewish performance medium first appeared just a few years after the full extent of the Holocaust in Europe became known.

Verbal slanging among members of the Friars Club, which was almost exclusively Jewish, was a retort to the prolonged insult and tragedy of Fascist Europe’s war against the Jews. In an era when a certain public decorum was expected, and indeed enforced by law, letting loose with naughty profane epithets was doubtless seen as liberating.

In this context, the targets or honorees were part of the mishpocheh and, as fellow performers, were flattered to be the center of attention. To be roasted by the Friars Club implied that a Jewish comedian had attained a certain level of eminence.

And so in 1950, the first-ever New York Friars Club roastee was Sam Levenson, a once-ubiquitous, perpetually grinning author of humorous memoirs of childhood travails in a Jewish immigrant family. Sentimental and ever-cheerful, Levenson doubtless relished good-natured taunts from his fellow Friars. In all likelihood, during his 15 years as a New York high school Spanish teacher, he had heard worse from some students.

The roast as an expression of affection was also seen the following year, when comedians Phil Silvers and Harry Delf were honorees. Delf was at one time considered so expert in his performance skills that he was entrusted with the job of teaching Fanny Brice (born Fania Borach, the original Funny Girl) how to speak with a Yiddish accent for a stage sketch.

In 1951, Mel Allen (born Melvin Allen Israel) the sportscaster and play-by-play announcer for the New York Yankees was roasted by the Friars. The tradition expanded through Yiddishkeit, with the trifecta of Jewish roastees in 1953 including Sophie Tucker, Milton Berle and Eddie Fisher. The following year it was the turn of comedian Red Buttons (born Aaron Chwatt), while at other roasts, the assailant-in-charge or roastmaster was Jack Carter (born Jack Chakrin).

Meanwhile, through the 1950s, Jews such as Jack E. Leonard (born Leonard Lebitsky) and Don Rickles honed their verbal aggression. Yet all of these entertainers hoped to flatter their audiences by focusing attention on them as they did on stars during roasts, albeit in a derisory way.

With time, roasts were televised, with varying success. The format became far less intimate than when it was shared among Jewish club members. Opened to the wider world, roasts could appear depersonalized, spotlighting protagonists for whom no real affection was felt.

The biographer Nick Tosches referred to the apparently random, disconnected famous people present at TV’s “Dean Martin Celebrity Roasts,” where an unconvincing laugh track added up to a “dais of despair.” Sometimes the actors or politicians who were given scripted lines to recite about the honoree were personally unknown to the latter. It was the opposite of the once-haimish community of the Friars.

“Comedy Central Roasts,” where the guests and speakers often expressed undiluted mutual hostility, represented a step further away from this sense of solidarity. Insults in the guise of jokes were routine. Jeff Ross (born Lifschultz), who frequently appeared on Comedy Central roasts, began to be hyped as the Roastmaster General.

Yet Ross’ blunt comedy stylings were not universally admired. In 2011, the venerable Jack Carter told an interviewer that he considered the roast of actor Charlie Sheen by Jeff Ross and others to be disappointing. There are “no roasters around anymore,” Carter kvetched. The elder comedian considered that Ross “stinks,” despite having published a self-laudatory book, King of Roasts.

Over the years, as the slanging became more extreme, politicians became increasingly dependent on writers, some of whom were Jewish comedians, for providing zesty put-downs of competitors. Even the stalwart Joan Rivers, who was never sparing in harsh words for fellow Jews like Elizabeth Taylor, expressed her dismay at the aggressive tone of a 2009 Comedy Central roast where Rivers was the central figure.

According to PBS and other news sources, one such 2011 roast might have motivated the current Republican nominee to run for the presidency. After Donald Trump’s relentless, although specious, accusations that Barack Obama was not American-born and therefore ineligible for the White House, President Obama responded with jokes at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner.

This public putdown, however deserved, reportedly sparked a desire for revenge that led to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue and all the tsuris that ensued. The nadir of these insults in the guise of entertainment might have been a 2016 Comedy Central show, ostensibly a roast of Rob Lowe, which turned into a serial excoriation of another guest, the conservative pundit Ann Coulter.

Although the bygone tradition of Jewish comedy roasts could be severe, a new level of cruelty was attained over the years. When viewed by humorless, and sometimes witless, right wingers who seek an audience response at any cost, these new spectacles of character assassination in the guise of comedy redefine the very concept of the roast.

In the minds of some observers, there may no longer be any tangible difference between the Jewish insult comedian and mere purveyors of insults. And so, the social and political fabric of America, which had once united groups of Jewish comedians, has unraveled.

Whether this societal cohesion can be reconstructed one day remains to be seen. Until that happens, the misconceived offering of barbs, purportedly as humor, will likely continue during electoral campaigns, betraying the original intent of past Jewish innovators in laughter.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I wanted to ask you to support the Forward’s award-winning journalism during our High Holiday Monthly Donor Drive.

If you’ve turned to the Forward in the past 12 months to better understand the world around you, we hope you will support us with a gift now. Your support has a direct impact, giving us the resources we need to report from Israel and around the U.S., across college campuses, and wherever there is news of importance to American Jews.

Make a monthly or one-time gift and support Jewish journalism throughout 5785. The first six months of your monthly gift will be matched for twice the investment in independent Jewish journalism.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO