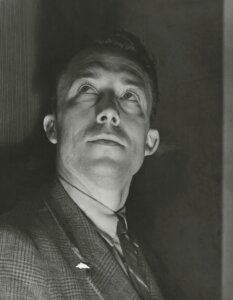

Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy, 1964. Photo by Getty Images

Red Scare: Blacklists, McCarthyism, and the Making of Modern America

By Clay Risen

Simon & Schuster, 480 pages, $31

On Feb. 8, 1950, Joe McCarthy, a still-obscure senator from Wisconsin, addressed a meeting of the Women’s Republican Club in Wheeling, West Virginia. The good ladies were not shocked by his warning that the American government was infested with Communist agents. After all, conservative Republican politicians and pundits had long been making such claims. But McCarthy went a step further, announcing that he knew the exact number and names of Communists in the State Department. Perhaps with a dramatic pause — we will never know for certain as the one recording was subsequently wiped clean — the swarthy, balding speaker then dropped a terrifying phrase: “I have in my hand a list.”

Few lines better capture the phenomenon of McCarthyism, born 75 years ago. It was a birth that was far from immaculate. McCarthy would never have gone so far — apologies to Isaac Newton — had he not leapt from the shoulders of fanatics, fools, and the fearful. In his meticulous and mesmerizing history Red Scare: Blacklists, McCarthyism, and the Making of Modern America, Clay Risen traces the cultural, political, and social forces that gave rise to McCarthy in 1950 and to his fall in 1954 — a fall that, though final for McCarthy, was anything but final for the politics of paranoia and resentment that he embodied.

Risen begins and ends his book with the story of Helen Reid Bryan, the executive secretary of a small New York charity, the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Agency, tasked with aiding Spanish Republicans who had fled Franco’s regime. We meet her in early 1946 when she appeared as the first witness called by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC). Claiming that Bryan’s employer was a front for Communist propaganda, the committee charged her with contempt for her refusal to turn over the charity’s records. At book’s end, we glimpse Bryan in 1951, completing the five-year jail sentence to which she had been condemned. Though this remarkable woman was no longer imprisoned, we learn that she could never entirely escape the financial, social and physical consequences of her experience — one that thousands of other Americans would soon also suffer.

By deftly toggling between the personal and national, Risen gives us a riveting and disquieting portrayal of our nation’s recent past and, perhaps, its immediate future. His narrative is driven, in part, by its most prominent characters. There are the truly admirable who, in the churn of public hearings and humiliations, held fast to their liberal ideals and constitutional rights. To name a few, there was Dalton Trumbo, the Hollywood screenwriter, who refused to name names and responded to the charge of contempt by warning the committee that this marked “the beginning of an American concentration camp.” (While Trumbo spoke, the committee chair kept pounding his gavel until it broke.)

Others include labor activist Harry Bridges who, though not a Communist, braved the hounding of the members of HUAC, but also anti-Communist labor organizations like David Dubinsky’s International Ladies Garment Workers Union. And, of course, Justice William O. Douglas, who along with Hugo Black, opposed the Smith Act, the broadly written anti-Communist law that destroyed the careers and lives of hundreds of teachers. Douglas warned his colleagues that, lacking evidence of subversive activity, the alleged crime of Communism “depends on not what is taught, but who the teacher is.” Overruled by the court majority, one which included Felix Frankfurter, Douglas concluded the justices were “now running with the hounds” of McCarthyism.

At the other extreme, there were the truly despicable like McCarthy — described by Risen as “an inveterate liar…who dressed like a slob, ate like a slob, talked like a slob” — and his lieutenant Roy Cohn, who pushed McCarthy “further than even he might have gone.” There also were more obscure figures who, driven by ambition or bile, fanned the fires of fear and paranoia already smoldering across the country.

Take Alfred Kohlberg, a textile manufacturer consumed by a mix of financial and ideological concerns, who funded countless anti-Communist groups and founded Plain Talk, a magazine that bristled with his ravings that Communists were already on America’s doorstep. Or if not Kohlberg, take Kenneth Wherry — please. A Republican senator from Nebraska, Wherry led the hounds in the direction of government officials rumored to be gay. Who could doubt, he asked, that “the Communists’ fifth column of Communists would neglect to propagate and use homosexuals to gain their treacherous ends.”

Finally, there were the tragic figures like Julius Hlavaty, an immigrant from present-day Slovakia who became the widely respected chairman of the mathematics department at the elite Bronx High School of Science. Hauled in front of McCarthy’s committee, Hlavaty swore he was not a member of the Communist Party, but he refused to discuss his earlier politics, telling the committee that one’s politics has nothing to do with teaching mathematics. Taking issue was Senator Everett Dirksen, who replied, “I think there is a subtle influence that goes out from your conduct and identity with organizations.” A short time later, Hlavaty and his wife Fancille, also a teacher, were fired by their school boards.

In a different register there is Sterling Hayden. A rising star in Hollywood, Hayden nevertheless enlisted in the Army in 1941. Promoted to the Office of Strategic Services, he was parachuted into Nazi-held Yugoslavia and worked as the Allies’ liaison officer with Tito’s guerillas. Once demobilized, an idealistic Hayden flirted with the Communist Party. Years later, frantic that he would lose custody of his children in a marital dispute, Hayden confessed this “crime” to the FBI and agreed to name names. Though he avoided the Hollywood blacklist, Hayden was always haunted, as he later confessed, by “the contempt I have had for myself since the day since the day I did that thing.”

Of course, Risen does not ignore the cases of Whittaker Chambers and Alger Hiss, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Though he does not uncover new facts or unveil new theories about these cases — historians have been raking this ground for decades — Risen recounts these events with great verve and a keen eye. A former true believer in Communism who became an equally fanatical anti-Communist, the furtive Chambers was as fearful — for good reason — of Soviet assassins as he was, judging by the alarming state of his teeth, of American dentists. The man he fingered as a Soviet spy, Alger Hiss, was an urbane diplomat draped in bespoke suits whose confidence often slid into condescension as he denied these allegations. The truth of the matter, Risen rightly notes, is less important than the era of hysteria it ushered in, one that has never since left us.

This claim makes for the urgent relevance of this book. In tracing the many political and cultural elements that, once combined, combusted into the Red Scare, Risen points not only to our past but also to our present, rightly insisting on what he variously calls the “throughline,” “genetic bits,” or “lineage” between then and now. The earlier era’s loyalty tests and surveillance tools, and threats of retribution and promises of rewards, the hounding of minorities and buckling of courts and the ascent of political con men and crumbling of constitutional and institutional guardrails have again erupted, like the plague bacillus, in our country.

How appropriate, then, that Risen quotes the conclusion of Albert Camus’ novel The Plague. The narrator, Doctor Bernard Rieux, warns that the plague bacillus never disappears and instead lies dormant in attics and closets for years until, one day, it again explodes into our lives. But take care: though this is the novel’s concluding line, it does not mean that we must resign ourselves to the plague. To the contrary, the conclusion that Rieux reaches — and we must recall — is that while victories over plagues never last, that is never a reason to stop resisting them.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO