Everything changed for Billy Barry the day that choreographer Ohad Naharin walked into the studio. Before that moment, the second-year Juilliard student imagined himself becoming a contemporary ballet dancer, probably in New York. Afterwards, all paths led to Batsheva, the acclaimed company in Israel that Naharin helmed and Barry had, up until then, known little about. As he put it: “Bat-what-va?”

Barry didn’t want to be in Naharin’s piece for Juilliard’s spring 2009 repertory show. It boasted the biggest cast on the program, and he had his eye on a trio by Twyla Tharp instead. To be one of only three people onstage presented a coveted opportunity for an aspiring young dancer. But shortly after he was chosen to dance excerpts from Naharin’s Max and Three, any sense of disappointment evaporated.

“We’re all in the room waiting for the rehearsal. It’s four o’clock. And then he comes into the room and it sounds cliché but he’s one of those people that, like, the air changes,” Barry recalled. Naharin — then the artistic director of Batsheva — sauntered in, sat down, and hung back, Barry remembered when we met at a cafe in New York last month. He imitated the choreographer’s nonchalant body language and observant gaze. “He hadn’t said anything yet,” Barry explained, but “this was the moment,” when indifference turned into intrigue. “Something’s going on,” he thought. “Who is this?”

Within days, Barry knew this was who he had to work with after Juilliard. “Ohad will love me,” he wrote on a piece of paper and tacked it to the spot above the mirror in his dorm that held his “mantras of the moment.” His sights were now set singlemindedly on Batsheva.

Two years later, the Long Island native who’d attended Catholic school through 8th grade packed his bags and moved to Tel Aviv. He’d spend the next 13 years building a successful career at Batsheva in a city known for its beaches and nightlife and a country known for its politics and wars.

Origin story

Barry was a teenager, buying a Coke in a bodega, when he got the call. At the time, he was a student at the Professional Performing Arts High School in Manhattan, training at Alvin Ailey nearby. He’d gotten into every college dance program he auditioned for except his top pick, Juilliard, where he was waitlisted. In the meantime, he’d deferred his acceptance to another school and snagged the part of Baby John in the European tour of West Side Story.

Then Juilliard called to tell him he was in. He was so excited, he practically wiped out an entire shelf of pasta. “I just got into Juilliard!” he cried in response to the clerk’s grumblings. “They’re like A, get out of here, and B, congratulations.”

Barry told me the story one Saturday morning after teaching a class in Gaga — the movement language developed by Naharin. He showed up still flushed from the exertion, waving his hands in front of his reddened face.

When Barry speaks, he doesn’t limit himself to words. His eyes might go wide, he’ll lean forward, gesture, get up from his chair. He’ll show you precisely how Naharin sat or reenact his exchange at the bodega. He’s hyper present and a locus of energy, talking and dancing his way through a conversation.

He fell in love with dance by accident when he was nine or 10 after seeing his sister’s best friend perform with a local studio. When he saw the tap piece, he turned to his mom and asked if he could do that. Tap classes begat jazz, hip hop, and ballet classes, leaving little time for other extracurriculars.

“I said goodbye to my initial dream of being an illustrator of children’s books to become a dancer,” he said. He stayed the course, moving up to Eglevsky Ballet on Long Island and then New York City. At the time, he said, “I was like 5’2”, 80 pounds, backpack heavier than me, falling over on the train, just going to the city to dance.”

Juilliard was the next step. Coming from the waitlist, he felt he had a lot to prove. He was growing fast, too, sometimes struggling to use his suddenly longer limbs. But it all started falling into place when he was cast in Naharin’s piece. One of the first things the choreographer did was cover the mirrors. “It felt very radical,” Barry said, but it made “more sense to me than being in the mirror and prioritizing how things look versus how things feel.”

Naharin was in town for the first and last few days of rehearsals, leaving the rest of the staging process to former Batsheva dancer Yoshifumi Inao. When the choreographer returned, Barry listened to him coaching students onstage, his voice guiding them from the dark theater.

He was “having people go again, again, trying to push things out of them and insisting, because he knows how to unlock people’s potential,” Barry said. The pressure upset some of the dancers. “But in real time watching individual progress over the course of seven minutes, I’m like, don’t get mad, you look great.”

When his turn came to show the “slow, melty bit” from his solo, “I remember so vividly, I left the line and got back in the rotation, and I hear, ‘Good, Billy,’” he recalled, imitating the low, accented inflection of Naharin’s disembodied praise spoken quietly into a microphone.

An American in Tel Aviv

When Barry told his parents he had to go to Israel for the Gaga Intensive that summer, he didn’t even have a passport. “I really didn’t know much about Israel at all, just that the job that I want is there,” he said.

He stayed by the beach, biking back and forth to the studios that August. “It was like gross hot, which I love and prefer,” he said. Those were the “best two weeks of my life until that point,” Barry said. “And over that summer, we kind of got to this arrangement that when I graduate, I’ll come to Batsheva,” he added. “All the parts of the road to getting there was just like, check, check, confirmation. Love, yes, good.”

Barry returned to Israel during his senior year to rehearse a duet for his final college performance. Naharin “told me to come to his office the next day and told me the news,” said Barry, who laughed, cried, and then called his mom. It was official: He’d be joining the Batsheva Ensemble — the junior company — in the summer of 2011.

Moving halfway around the world went pretty smoothly, especially since he lived with another Juilliard grad who’d also joined Batsheva. But there was also some culture shock.

“In the beginning, I used to think everybody was screaming at each other,” Barry said. “It felt harsh, the language and the energy, before I realized people were like, ‘I love you’” — loudly expressing their affection, not anger. He got used to the bureaucracy of banks and the dynamics of waiting in what could hardly be called lines. “I learned to be more assertive,” he said, to avoid becoming “a foreign pushover.”

He found more confidence in his dancing, too. He grew up at Batsheva, where “as much as things have to be precise, we’re not expected to be like carbon copies of each other,” he said. “Personal interpretation is so encouraged.” It was there, he explained, that “I found out what I thought was exciting about myself and now it’s one of my strongest qualities.” He can get up onstage and improvise without questioning what he has to offer.

Barry moved up to the main company in 2012, and spent the next dozen seasons creating, rehearsing, and performing with Batsheva across Israel and all over the world. He danced in iconic works including Kamuyot, The Hole, Anafaza, Three, 2019, Last Work, Hora, and MOMO, which recently toured the U.S. after Barry’s departure. And he rose in the ranks to become the company’s assistant rehearsal director.

Outside Batsheva, Barry rotated through side gigs that delineated different eras of his Tel Aviv life. He was a faux keyboardist — he didn’t know how to play but they liked his look — for the band Tiger Love, which opened for the Pet Shop Boys in Tel Aviv. He produced a line of parties with fellow American Batsheva dancer and Juilliard grad Shamel Pitts. And he bartended at a favorite local spot near the Suzanne Dellal Centre for Dance and Theatre, serving drinks after shows and eliciting double takes from patrons who’d just seen him onstage.

But there is, of course, more to living in Israel. The sirens warning of incoming rockets were terrifying. “The first few times I was by myself and just would go where I saw people,” he said. He was amazed at how quickly he became numb to it, though. “It’s so draining to be upset all the time. The easier thing to do is just give into it being part of your day, which is sad and fucked up. But what else are you gonna do?”

He didn’t realize, for years, that not all dance companies tour with a security guard who checks the bus before artists board. And most companies aren’t regularly met with protests. “We rehearse these situations,” Barry said, practicing how to pause the show, sometimes even having the ushers pretend to escort someone out.

“Usually inside, they’ll just chant or shout,” Barry said. But at a performance in Lyon in 2022, the protesters came onstage. He pulled up a video on his phone to show me the scene: Two men stepped right up into the otherworldly green glow of Hora and started running around the stage with Palestinian flags just as Barry was finishing a solo.

“I looped the move because I was like, I don’t know what’s going to happen here,” he said, repeating the same small step over and over while waiting for a cue to exit the stage. Wherever Batsheva goes, protests are likely to follow. “This is part of it,” he said.

False goodbyes and a proper finale

The mantra Barry taped above his mirror all those years ago came to fruition. He built a long, successful career at his dream company, working with the choreographer who sauntered in one day and set him on a new trajectory.

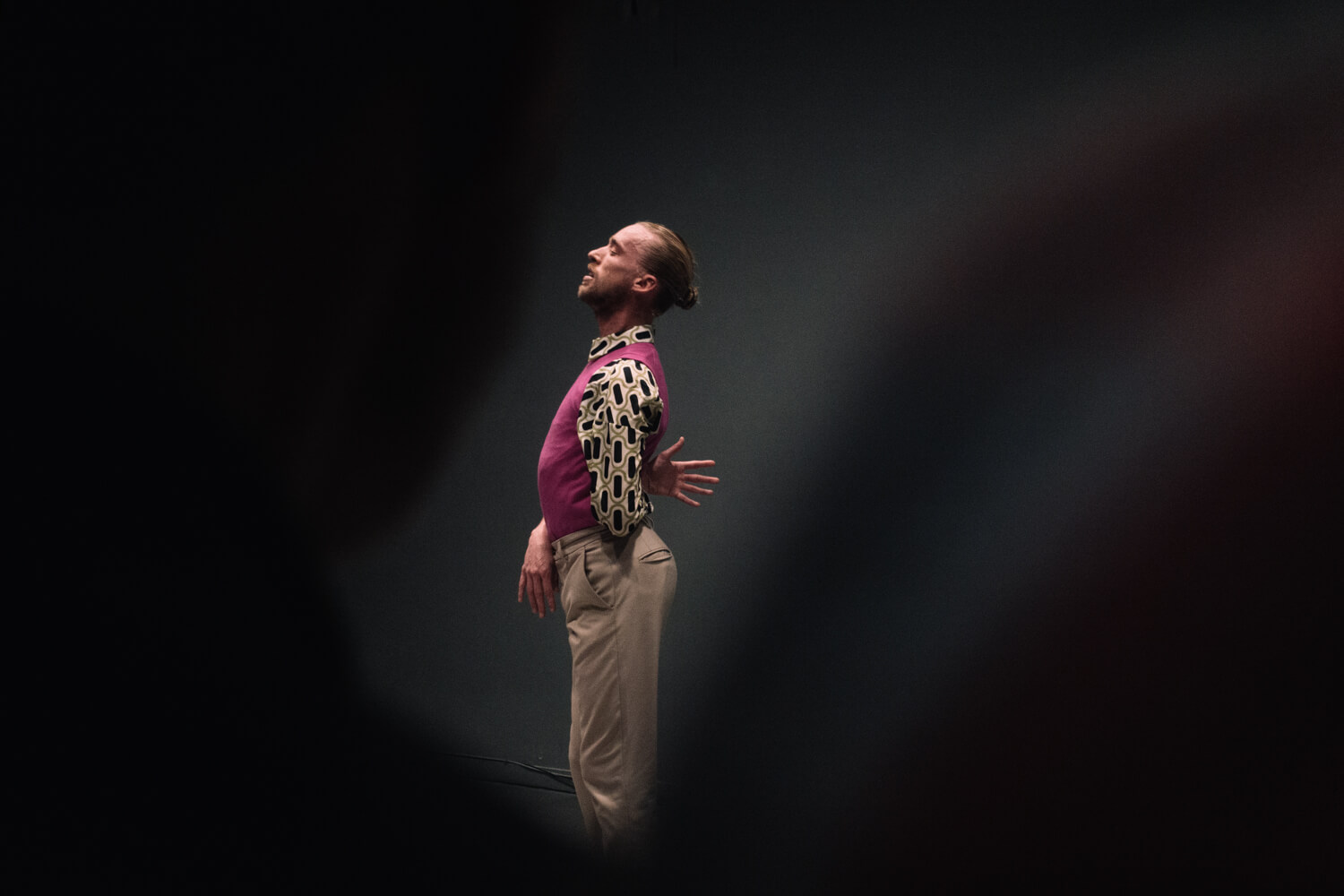

For years, Barry was an immediately recognizable and striking figure onstage with Batsheva. It would be hard to miss his blond hair pulled into a bun, his lanky frame — once described as “his reedy, praying-mantis-like body” — and his distinct movement quality.

In an email, Naharin called Barry “highly creative and a remarkable interpreter of my work,” citing his “great sense of humor, high intelligence, exceptional musicality, and coordination.” In his eyes, “Billy is a unique and rare artist.”

There’s a particular moment that sticks in Barry’s memory. One day, a fellow dancer walked in and casually asked a probing question, as Israelis sometimes do: “What is your dream?” His first reaction was “It’s 11 a.m., chill out.” But then he began to consider the question for real. “I was thinking like, I got it, I’m living it,” he said. “That also got my brain going. What do I want to do next?”

That question percolated for a long time before Barry had an answer. “My life is in thirds: childhood, school, and Israel. It became so much more than the job. That’s where my adult life started,” Barry said.

“There were a couple false endings, one of them during COVID,” he explained, when Israel’s strict lockdowns hit hard. Barry taught Gaga online, which kept him busy but also burnt him out. At one point he gave his notice, but was so full of regret that he changed his mind. He didn’t want his Batsheva story to end on a “dreary COVID note.”

It’s a good thing he stayed, he said, because that’s when Gianni Notarnicola was promoted from the Ensemble. “He came up to the company and resparked my desire to choreograph,” said Barry, who in 2022 began collaborating with Notarnicola — an outlet that eventually helped usher him to a new chapter.

There soon came another moment that could have made for the wrong ending. When Barry woke up in Israel on Oct. 7, he had “50 missed calls, like 1,000 texts,” he said. “I knew it was different because everything shut down.” He spent a couple months in Italy and New York. Some American friends didn’t understand why he’d go back.

“I didn’t think twice,” he said. “It’s been too long to let it finish like this.”

Barry finally announced last April that he’d be leaving Batsheva in July. And he got a proper finale, performing Naharin’s Three at Suzanne Dellal. “It was the first piece I had ever seen the company do in that theater, and it was the last one that I did. Everything about it and around it felt really full circle,” he said. Friends from over a decade in Tel Aviv filled the audience and he was cast in a duet with Notarnicola.

“It felt all very scripted by life,” Barry said. “This was how it was supposed to be.”

‘Wonderland’ to ‘Wonderland’

When we sat down for an interview in late March, Barry was between new adventures. He’d just returned from London, where he worked as an assistant choreographer for FKA Twigs’ tour. Two weeks later, he was off to Italy to dance with Notarnicola and prepare for a summer tour of their own.

But he’s also had a few more full circle moments. One of his first freelance gigs after returning to New York was to perform with Gallim Dance Company last November in Wonderland, a production he’d been p—art of in 2010 while still a student. The next month, he reprised his role as the host in Anafaza as a guest with Batsheva. And after our interview, he was heading to meet a Juilliard student whose senior solo he’d be choreographing.

Barry shows up “with so many ideas, and so much energy, and a lot of joy,” said Gallim artistic director and choreographer Andrea Miller, also a Juilliard and Batsheva alum. When she learned Barry was on his way back, she said, “a reunion had to happen.”

He was drinking a little less Diet Coke, Miller joked, but he was still just as joyful, hilarious, loyal, perceptive, expressive and authentic as he’d always been. And he’s matured as an artist. “There was a certain very confident understanding of his craft,” said Miller, who’s asked Barry to be part of her fall premiere and is eager to see him explore his own choreographic aspirations. “He has a lot to give.”

Barry can see how far he’s come, too. Once upon a time, his attitude was, “tell me what to do, and I’ll do it, and I’ll be quiet,” he said. Returning to Wonderland 14 years later, he was a seasoned artist being asked to offer choreographic suggestions. He felt an urge to pass on some of what he’s gleaned to the younger dancers in the room.

“You have a voice,” he told them. “As much as people could think that a dancer’s job is to shut up and do it, I know that that’s not the case. Or doesn’t need to be the case. Or if it is the case, that’s not the room that I need to be in.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO