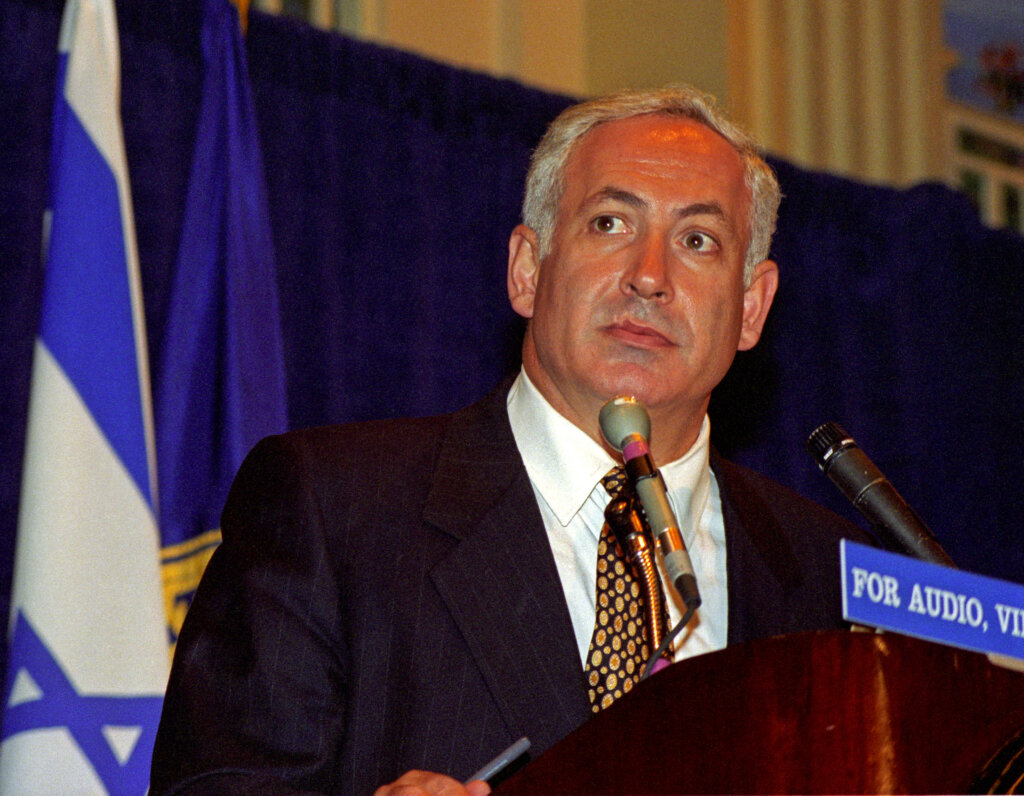

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu addresses a press conference in Tel Aviv on July 13, 2024. Photo by Nir Elias / Pool / AFP / Getty Images

There are moments in a nation’s story when its fate appears to rest in the hands of a single person — when one figure can determine whether the country will rise, stumble, or fall. That is Israel’s unfortunate situation today with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Netanyahu’s cumulative 18 years in power make him the longest-serving leader in Israel’s history. Yet to many of his own people he is a threat — a man seen as steering the country toward moral collapse, strategic folly and democratic decay. A brilliant politician who remains tireless and potent and still revered among his hard core of followers, Netanyahu, 75, seems convinced that his rule is essential and must be perpetual. He has become, to many, a cautionary tale — the very embodiment of the corrupting effect of power, which transformed an extraordinary young man into a hardened and heartless authoritarian.

In the course of interviews with Netanyahu over his decades at Israel’s political forefront, I’ve witnessed that transformation firsthand.

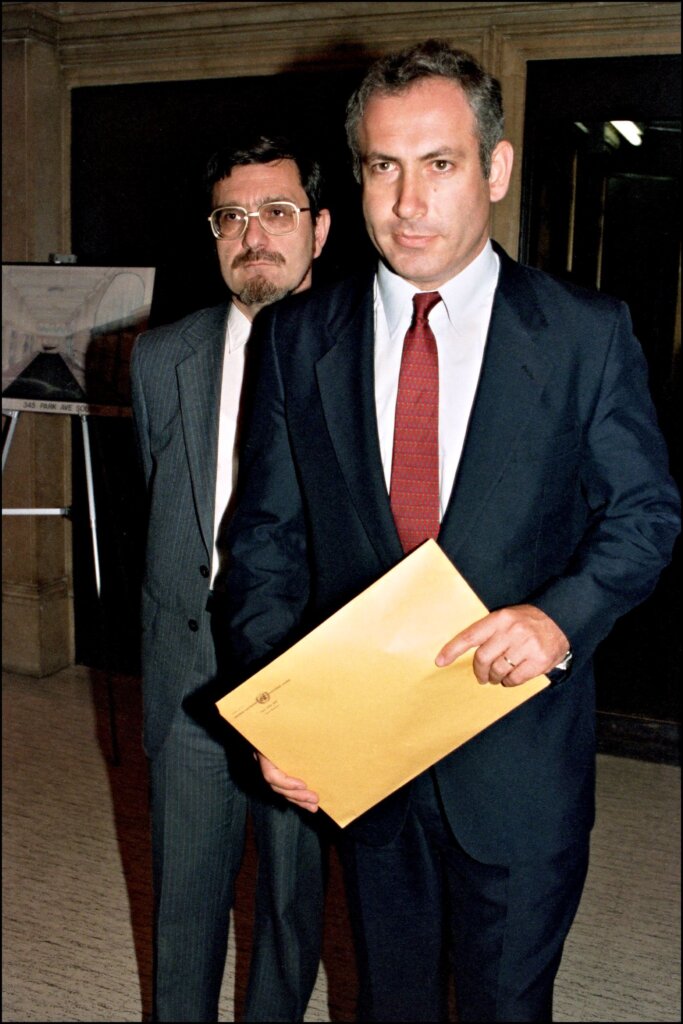

I first learned of Netanyahu in the mid-1980s when I was a student in the U.S., watching ABC’s Nightline with Ted Koppel. Netanyahu, then Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, was a regular guest. But his biggest claim to fame at the time was his brother, Yoni, the late hero of the extraordinary Entebbe hostage rescue mission. A former commando in his own right, Netanyahu projected intellect, clarity and strength.

His English was flawless, almost unaccented, but with just the right trace of foreignness to make him seem impressive as a non-American, despite his early years spent living in Philadelphia. I suspected that he was wily enough to actually feign the subtle semi-foreignness — that’s how manipulative he seemed, even then. He was dogmatic, but approachable; Koppel could easily converse with him. And despite a surface harshness, he often had the trace of a smile — hinting at humor, perhaps also self-awareness.

Only a few years later, in 1988, I interviewed him for the first time. I was writing for The Jerusalem Post about demographics and Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza; he had just returned to Israel. It amazed me that Netanyahu joined the right-wing Likud party, and that such a smart man seemed to support some Israelis’ aspirations to incorporate the West Bank and Gaza.

When we met, I asked how he could square that position with the fact that Israel clearly could not remain both Jewish and democratic while absorbing so many millions of Palestinians.

He dismissed the concern with flourish, citing with dazzlingly absurd precision the “interplay of eight variables” including birth, death, immigration, and emigration on both sides. He predicted mass Palestinian emigration after economic shifts that would naturally reduce their ability to find jobs. History has proven him wrong on every count, and today the combined territory is half-Arab — but his delivery was mesmerizing. It was nonsense — but nonsense that dazzled at the level of a superpower. I remember thinking: Here is a man who can sell snake oil with conviction. A gifted communicator who could lead a movement — but where to?

The demagogue emerges

In May 1996, I was working for The Associated Press, and Netanyahu had ascended to lead Likud; he was campaigning against incumbent Prime Minister Shimon Peres. I was dispatched to speak to him days before the vote.

Peres had led early in the campaign, riding a sympathy wave after the Nov. 1995 assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, the climax of a vicious incitement campaign led by Netanyahu himself. But a Hamas campaign of bus bombings had led many Israelis to sour on peace, and Netanyahu was closing the gap.

I asked him what final status he would offer the Palestinians as part of the Oslo Accords — which were supposed to reach a final resolution in 1999 — if victorious.

“Young man,” Netanyahu replied, “I will offer them autonomy.”

But the Palestinian Authority already was an “autonomy” government, I protested. “They want independence.”

“Young man,” he repeated, as if to establish a comparative maturity — he was 46 — “have you heard of the Catalans?” This Iberian tribe, he explained, tolerated living under an autonomy arrangement, and even embraced it.

Sure, I said, but the Catalans were also full and equal citizens of Spain who vote for the same parliament as everyone else. Was this what he would offer the Palestinians — giving them, based on demographics, the ability to elect about half of the Knesset?

Netanyahu looked around, saw there were no TV cameras, told me “I’ll be back,” and was gone.

Yes, Netanyahu seemed foolish to me, because his analogy was laughably inapplicable. But he understood that few listeners would have seen that. His goal was not a professorship in comparative politics, but votes. And his method of selling snake oil, then as now, was combining confident eloquence with arguments that sound just plausible enough.

This works. It worked in 1996, when he successfully upset Peres by a whisker and began his first three-year term as Prime Minister. And it’s worked, with some gaps in efficacy, ever since.

The seven sins of Netanyahuism

In our third interview, when I was AP’s Jerusalem bureau chief in 2002, I found a darker, angrier Netanyahu. He had been defeated by Ehud Barak in the direct election of 1999, amid continuing terrorism and general unhappiness with the dead end on both the Palestinian issue and the continuing occupation of south Lebanon. By this time Barak, too, was gone, and Netanyahu was languishing as finance minister on the sidelines of Ariel Sharon’s government. He was as colorfully articulate as ever — memorably, he called the Palestinian Authority a “corrupt, backward, primitive regime” — but also radiated a brooding suspicion that bordered on the hostile.

Much to Netanyahu’s dismay, Sharon was proving popular. The press was largely against Netanyahu, and he had taken to returning the favor.

But he used his role in the government to do something very right. A committed free marketeer, he bravely slashed subsidies that had disproportionately benefited the Haredi sector, in hopes of nudging them into employment. The Netanyahu who took that move is nowhere to be found today. Now, his far-right government depends on the support of Haredi parties, so he is pursuing the very opposite policy — which, as the community quickly grows, will drive the economy off a cliff.

Hypocrisy is often assumed of politicians. It is, in some sense, priced in as part of the craft. But rarely is it displayed at a level so sublime as it has been throughout Netanyahu’s career.

His attitude toward the Haredim is only the start. In 2009, he demanded that Prime Minister Ehud Olmert resign because of a police investigation.

“A prime minister up to his neck in police investigations,” he told Israeli TV with his customary confidence, “has no moral and public mandate to determine critical things for Israel, since there is a not unfounded concern that he will decide based on his personal interest — for his political survival, and not in the national interest.”

Now, of course, Netanyahu himself is not merely under police investigation; he is actively on trial for bribery, fraud, and breach of trust. And still he clings to power, making calls of national consequence while under the most severe legal and ethical cloud. There is a “not unfounded concern” by millions of Israelis that these decisions — like resuming the Gaza war a few weeks ago, as demanded by his far-right allies — aim to ensure his survival, at any cost to his country.

Indeed, Netanyahu has made many of the most pressing issues Israel faces worse, while overseeing a desperate erosion of public norms, institutional health, and social cohesion. Judging by the state of play today, these are the core failures — it would be fair to call them the seven sins — that will define his legacy when he finally does depart:

- The impending binational state: From my 1996 interview with him up to today, Netanyahu never stopped denying the obvious demographic threat of indefinite occupation. He has done everything possible to block Israel from separating itself from the Palestinians. Instead, under his watch, settlements have expanded in the West Bank, with full Israeli annexation a looming threat. And now, the number of Jews and Arabs in the land between the river and the sea is just about equal. There is no Jewish majority for a theoretical country in which Israel absorbed the West Bank and Gaza. Nor is there a plan. Only a creeping reality of unequal neighbors, and the long shadow of international condemnation and unending sectarian strife.

- Favoring Hamas over the Palestinian Authority: Netanyahu-led Israeli governments have often undermined the more moderate — if dysfunctional — Palestinian Authority, even allowing Qatari cash infusions into Hamas-run Gaza. Their goal was clear: Keep Palestinians divided, and thus make peace negotiations impossible, allowing Israel to continue encroaching on the West Bank, and Netanyahu to tighten his hold on power. The tragedy of Oct. 7, 2023, when Hamas breached Israel in the worst attack on Jews since the Holocaust, revealed the unbearable cost of that strategy. And Netanyahu has since resisted calls for a commission of inquiry into his role in setting the stage for that horrifying assault, which has been de rigueur in far lesser disasters. For Netanyahu, accountability has always been for others.

- The Haredi national suicide pact: Netanyahu is by now completely in league with the aforementioned Haredi parties, which are in a massive conflict with the rest of society. The Haredi community, which overwhelmingly refuses to serve in the military and has low labor participation, is growing explosively, with almost seven children on average per family. They now make up a sixth of the population, and are doubling as a proportion every generation. They refuse to have their youth study secular core curriculum subjects that would make them employable in a modern economy, are dependent on welfare, and insist on long years of seminary studies at taxpayer expense. Netanyahu, who has no majority without their political support, has become their main enabler. The result is a demographic time bomb. Unless the dynamics change, there is a future majority that rejects the values of modern Israel.

- The corruption: Netanyahu is on trial for bribery, fraud, and breach of trust, and further scandals loom. The details are lurid: gifts of champagne and cigars, dirty deals with media moguls, and strange business dealings involving cousins and cronies (charges he dismisses as fabrication amid a campaign of vilification against the police, the prosecution, the court system and the media). His wife has convicted for misuse of state funds, and been sued repeatedly by staff for verbal abuse. His government is rife with scandals. Among them: Two of his close aides are currently under investigation for reportedly taking money from Qatar to besmirch Egypt. It is a breathtaking landscape of skullduggery and corruption, all of which Netanyahu dismisses as a witch hunt by a so-called “deep state” — a phrase imported from President Donald Trump’s MAGA movement in the United States.

- The politics of division: Israel has never been so bitterly polarized as it has become under Netanyahu. That’s intentional. Netanyahu’s method is not to build consensus, but rather to destroy rivals, and to provoke disunity, which tends to make his strongman messaging more appealing. He has incited against prosecutors, judges, journalists, fellow politicians — and now the security establishment. He has systematically attacked the legal system with such ferocity that some of its officials required bodyguards; as one example, on the day his bribery trial opened, he held a press event in the courthouse, surrounded by silent lackeys, insisting that the legal system was part of a left-wing plot against him. The damage to national cohesion may be irreversible.

- The obsession with power: No principle, no promise, no ally is safe from Netanyahu’s need to stay in power. He has brazenly violated political promises, such as when he engineered a way out of his agreement to rotate the premiership with moderate Benny Gantz in 2021. He persuaded Haredi rabbis to back out of a critical education reform they were about to support, in order to deny then-Prime Minister Yair Lapid a success story. He promised to maintain Likud’s historic refusal to form governments with the racist far-right, then made them his key partner. Now that he’s on trial, he’s trying to destroy independent judicial oversight with “reforms” that would enable the government to control judicial appointments and give parliament the right to strike down rulings. He refuses to legitimize rivals who defeat him in elections — including by repeatedly boycotting, as opposition chief, standard meetings with Lapid. This isn’t ideology. It’s pathology.

- The erosion of democracy: Even beyond the judicial overhaul, Netanyahu has been trying to erode liberal democracy for years. A main feature of his efforts are his attacks on the parties representing Israel’s 2 million Arab citizens. Each election cycle, his Likud Party tries to ban them in Knesset committees, an effort that is promptly overturned by the Supreme Court. In a particularly shameful episode, on Election Day in 2015 he issued a video warning his supporters that the Arabs were voting “in droves” — a clear incitement. He is obsessed with media criticism and is constantly browbeating the media as his enemy, and trying to establish greater political control over the independent press. He is currently trying to fire a series of public servants who have refused to fall in line with dubious maneuvers by his government. The overall effect: A radical chipping away at Israel’s institutions that will take years to undo.

A crisis approaches the boiling point

The last time I met Netanyahu was in 2018. Then AP’s Cairo-based Middle East editor, I got to ask the highly coveted first question at his annual meeting with the foreign press.

I asked the prime minister whether it truly did not bother him that the overwhelming majority of his own peers — secular, educated Israelis — opposed him with increasingly urgent vehemence, and considered him nothing short of a menace.

“They not only oppose you, but they think you are leading the country to absolute and irreversible ruin,” I continued. I told him the toxicity was unbearable, and asked if it was truly possible that this dynamic didn’t bother him at all.

Netanyahu ignored the question and asked me whether I wanted to switch places — “because it sounds to me as if you want to be the one who is on stage.”

Amazingly, Netanyahu is still there. He clung to power through several inconclusive elections, was actually replaced for a year and a half by Naftali Bennet and Lapid, and then scraped through in 2022, due to splits in the opposition that caused 6% of its vote to go uncounted. His current term has been a train wreck, with his proposed judicial overhaul ripping society apart, and then the Oct. 7 Hamas attack and the devastating war that followed. Any other prime minister in the country’s history would have resigned; Netanyahu clings madly to his seat, seemingly indifferent to the fact that most Israelis now adamantly object to his regime.

In recent weeks, Netanyahu’s government has pushed to remove Attorney General Gali Baharav-Miara and Shin Bet chief Ronen Bar — moves widely seen as efforts to block investigations into suspected corruption by Netanyahu and his government, including the alleged payments linked to Qatar. Both Baharav-Miara and Bar have resisted, warning of political interference in national security.

The firings have sparked a fresh wave of protests against Netanyahu, and are likely to end up before the Supreme Court. Former Supreme Court chief justice Aharon Barak, an icon of Israeli liberal democracy, recently warned that all this may explode in violence. “The main issue facing Israeli society is … the deep rift among Israelis themselves. This divide is worsening, and I fear it will be like a train going off the rails, spiraling into an abyss and leading to civil war,” he said.

This is all Netanyahu’s doing, and while he may never acknowledge it, I think he knows. Back in 2018, when he brushed off my question, I noticed a subtle but significant change in him. The smile I remembered from his Nightline appearances was gone. The humor had curdled into a bitter cynicism, as humor often does, when a person feels beset by enemies from all sides.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a Passover gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO