Some of the Hollywood Ten in 1950, from left: Samuel Ornitz, Ring Lardner Jr., Albert Maltz, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Herbert Bieberman and Edward Dmytryk. Courtesy of PhotoFest/The New York Historical

Fascism wasn’t always a bad word in the U.S.

In the 1940s and 1950s, one of the charges levied by the House Un-American Activities Committee was “premature antifascism.” Largely directed at people who had opposed the Nazis and Franco during the 1930s, before the U.S. had entered World War II, the label was used to smear activists as Communist radicals — even though their opposition to fascism had eventually aligned with U.S. policies. Those charged had been dangerously ahead of the curve.

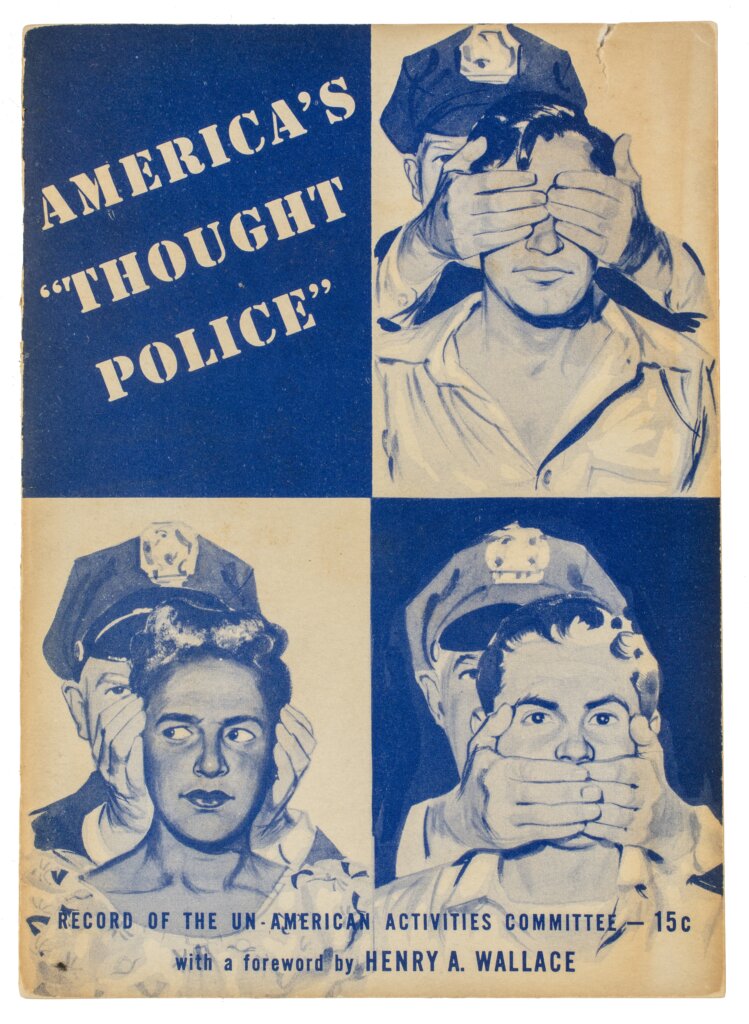

A new exhibit at the New York Historical — Blacklisted: An American Story — explores the Red Scare era of American history through posters, newspaper clippings, political pamphlets and video clips from the time. While Joseph McCarthy eventually lent his name to the defamatory smears that characterized the period, the exhibition shows the persecution of anyone with the taint of radicalism began far before his election to the Senate in 1947; the House Committee on Un-American Activities was established in 1938 to weed out subversive activities and communist ties among government officials and private citizens alike.

racial justice. Courtesy of The Unger Family/The New York Historical

Blacklisted, and the Red Scare generally, has obvious echoes today, with the Trump administration’s crackdown on immigrants accused of gang violence, based on the thin evidence of their tattoos, as well as the White House’s targeting of activists involved with the pro-Palestinian movement. But the exhibit actually debuted years ago at the Jewish Museum of Milwaukee; the New York Historical has been working to bring it to the city for two years.

“Obviously, it could not seem more timely today,” said the president and CEO of The New York Historical, Dr. Louise Mirrer, over the phone. “But two years ago it also seemed quite timely. Mainly because we’d begun to see book banning around the country, questions about what teachers were teaching in their classroom, and many other instances of curtailment of various First Amendment rights.”

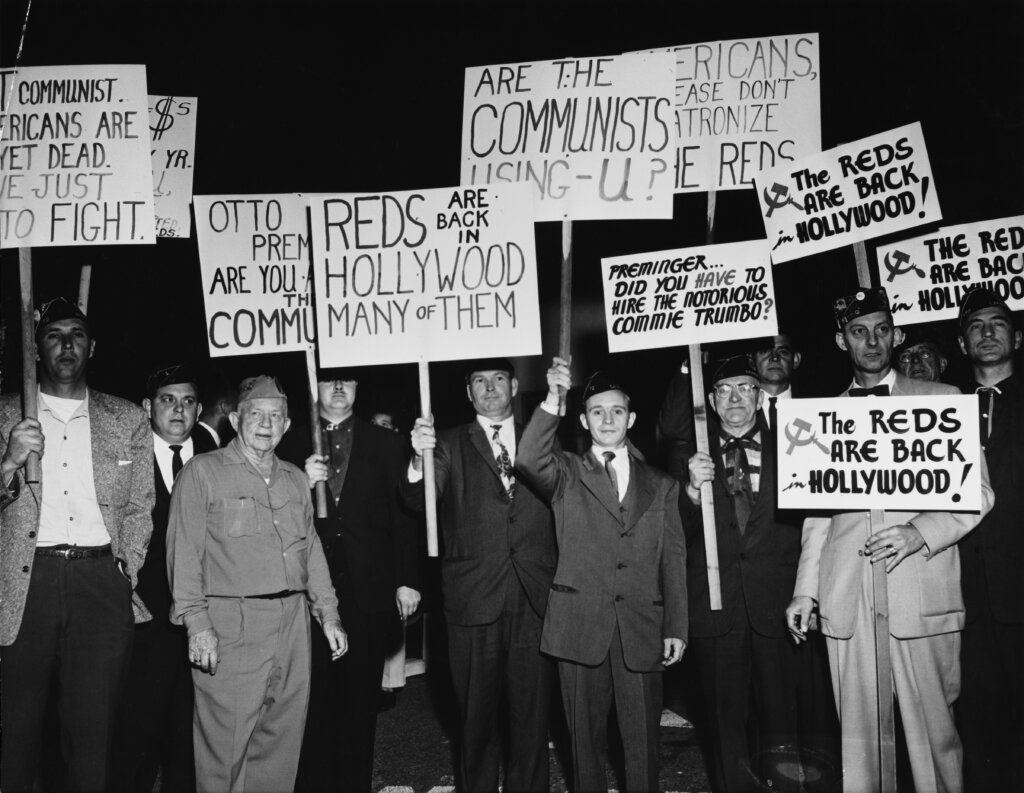

Blacklisted focuses on the so-called Hollywood Ten, a mostly Jewish group of screenwriters and directors who were jailed after refusing to testify before the Committee. In a tour of the exhibit the day before it opened, coordinating curator Anne Lessey told me that Hollywood got particular attention from HUAC thanks to “a heightened understanding of propaganda in the wake of World War II.”

But through the lens of the Hollywood Ten, the stifling effect of the far-reaching atmosphere of fear is clear. During the period of HUAC’s influence, names were blacklisted on the basis of mere association with a liberal cause — which included labor organizing and support for the Civil Rights Movement, both causes that were endorsed by the Communist Party USA, but also held wide appeal, particularly within Jewish and Black communities.

Anyone who wasn’t a “descendant of Mayflower Americans” was considered suspicious, Mirrer said. “Their names didn’t sound American, their appearance, you know, was different.” That was enough to investigate them.

The FBI also kept files on anything with the faintest hint of criticism of the American status quo. The exhibit excerpts files for movies including It’s a Wonderful Life — accused of “a rather obvious attempt to discredit bankers” that “deliberately maligned the upper class” — and Crossfire, a 1947 film noir about antisemitism in post-WWII America, directed by Edward Dmytryk and produced by Adrian Scott, both members of the Hollywood Ten.

“The racial angle has been unduly emphasized,” the FBI file on Crossfire says. “This picture is near-treasonable in its implications.”

One of the most striking documents in the exhibit is a yellowed, typed statement prepared by Samuel Ornitz, one of the Hollywood Ten, which he was not allowed to deliver to the Committee; unlike in court, the House hearings did not allow people to defend themselves, and so-called “unfriendly witnesses” like Ornitz were only allowed to answer two questions: “Are you a member of a professional guild?” and “Are you a member of the Communist party?”

In the never-delivered statement, Ornitz opens by saying that he wishes “to address this committee as a Jew,” calling out one of the congressmen on the Committee, Southern Democrat John Rankin, as an “outstanding antisemite” who “revels in this fact.” (Rankin had defended the Ku Klux Klan as “an old American institution,” saying that the “threats and intimidations of the Klan are an old American custom like illegal whiskey-making.”)

Ornitz says that Hitler used the same smears of communism as his “poison weapon” to curry national hatred, referencing what he observed during his Army service in World War II. “When constitutional guarantees are overridden, the Jew is the first one to suffer,” he wrote. “But only the first one.”

At first, Hollywood fought back, certain of their right to free speech; stars like Lauren Bacall and Gene Kelly formed a group called the Committee for the First Amendment and flew to D.C. But, quickly branded as “Reds,” they soon backed down. And, most damningly, in a secret meeting at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel, a group of Hollywood studio executives — including Jewish men like Samuel Goldwyn and Louis B. Mayer — decided to self-enforce the blacklist in an effort to protect their studios.

This is perhaps the most important takeaway from the exhibit: Ultimately the consequences of the Red Scare were delivered voluntarily, by everyday people. Leaders across industries created their own blacklists and refused to hire or associate with anyone with the faintest whiff of radicalism; coworkers, neighbors and even occasionally spouses named names in an effort to protect themselves from the destructive accusations. HUAC would have been far less powerful without the success of its fear-mongering on the nation, whipped into an anti-Communist fervor.

Eventually, the hysteria faded, and HUAC’s influence ebbed. The Supreme Court, which had previously declined to overturn the Hollywood Ten’s contempt charges, ruled in favor of an organizer with the United Auto Workers who had refused to inform on his colleagues. In the decision, Chief Justice Earl Warren castigated HUAC and asked: “Who can define the meaning of un-American?”

Today, as accusations of antisemitism are lobbied about freely with disastrous consequences, and any research on gender, immigration, history or science that doesn’t align with the Trump administration’s priorities is met with canceled government contracts, it’s hard not to see the parallels. And those worried about the rising authoritarianism are, today too, told they are prematurely applying the label of fascism. The scare might not be red this time, but it’s just as present — and just as chillingly, it’s being enforced by everyday people.