A photo taken July 28, 1906, shows Jewish agricultural settlers mingling with gauchos and soldiers. Courtesy of YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

A forgotten folk ritual, widespread in Jewish communities of Eastern Europe, saw residents assemble on the Shabbat before Passover outside the doors of men afflicted with fungal infections of the scalp.

Once there, those in the crowd might hand the men a mock one-way ticket to Egypt, which read, “the journey is free. Attention: It is forbidden to scratch yourself on the way.” (These men with favus or, in Yiddish, parkh were targeted for their condition’s resemblance to the biblical plague of boils.)

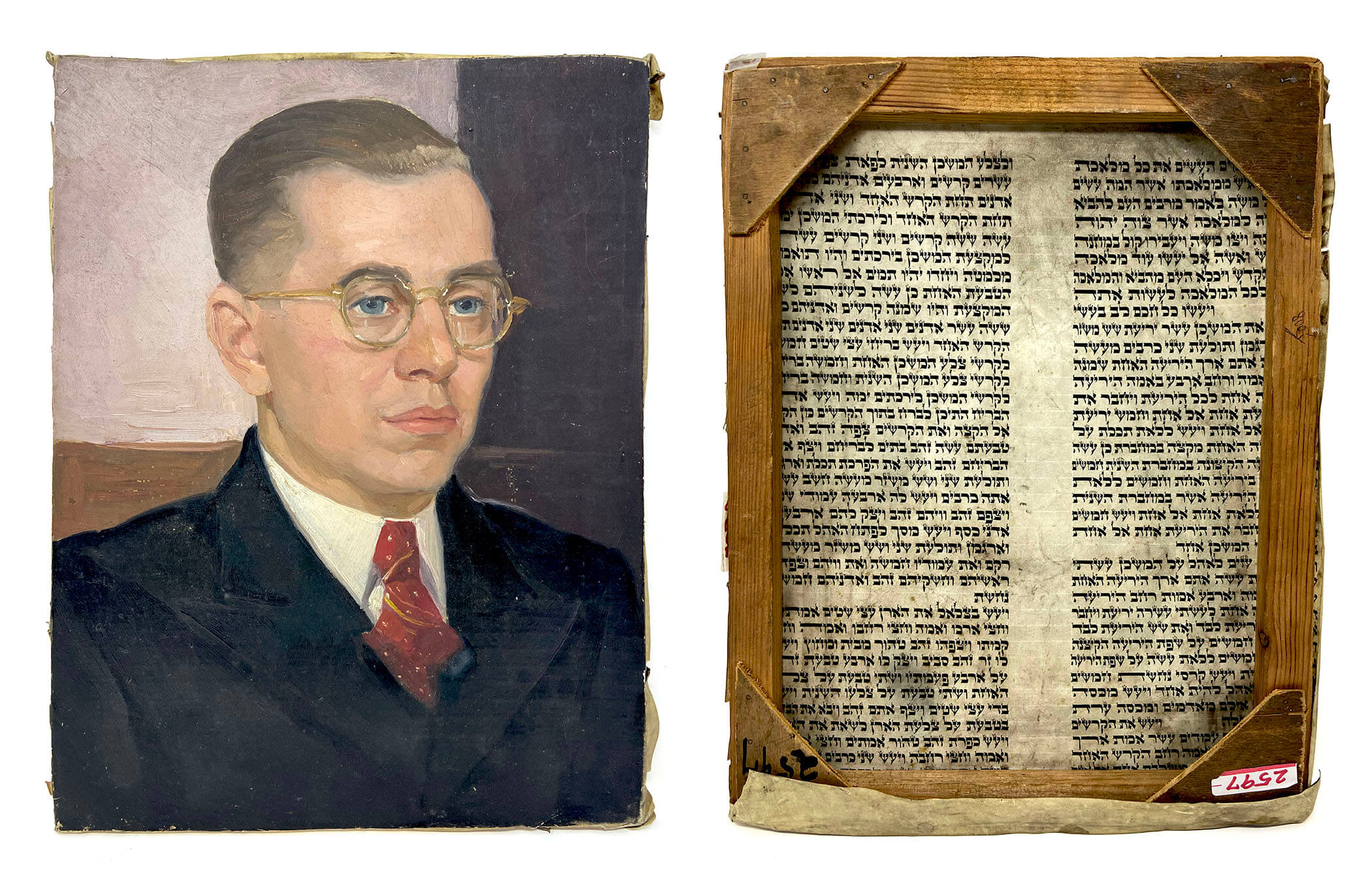

One of these tickets, a record of this cruel tradition, belongs to the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, alongside 24 million other artifacts. The archive contains what its founders envisioned 100 years ago when it was established in Vilna: a repository for Jewish life and culture, even its challenging parts.

“Each of these objects asks questions, provokes, drives memory, incites reflection,” YIVO’s CEO Jonathan Brent wrote in the preface to 100 Objects from the Collections of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, a new centennial publication out June 22.

Edited by YIVO Archive director Stefanie Halpern, with accompanying essays from scholars, the book is divided into topics of beliefs and customs, labor, the Holocaust and its aftermath, immigration, arts and culture, history, the written word and YIVO’s own development.

Singular objects, like Yiddish literary titan Chaim Grade’s typewriter, are accounted for, as are mass-distributed artifacts like an early issue of the Yiddish Forverts. The most compelling objects challenge a narrative of Jewish life often rendered as flat and sepia-toned.

For every image of children at Cheder in the Pale of Settlement, there is another that shows Jewish emigrants in the pampas of Argentina, in the company of gauchos and soldiers. The tragedy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, is represented here by a piece of sheet music, a tune likely — and cynically — adapted by Yiddish musicians from a popular genre of songs about orphans. There are clerical papers from an Auschwitz subcamp, but also meticulous, hand-painted graphics documenting library usage in the Vilna Ghetto.

If we may feel distance from folk customs, gathered in Europe by YIVO’s network of volunteer zamlers (collectors), the book also touches on recent history, in the form of a menorah bong crafted in 2019 in Austin, Tex. But even the most ancient objects in the collection point to continuity in ways we might not expect.

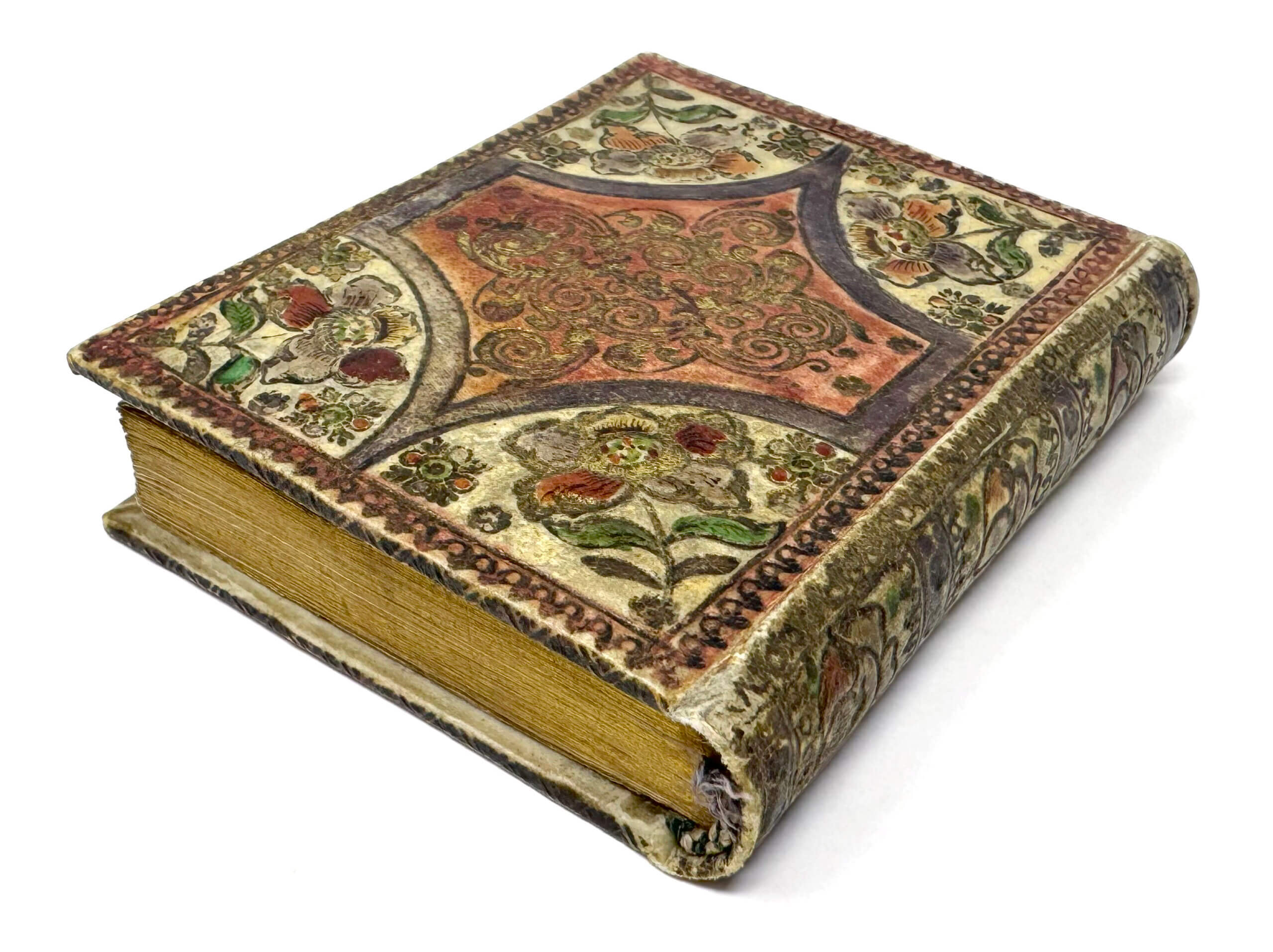

A tractate concerning Jewish monetary law from the Babylonian Talmud, scribed in 1721 by a 12-year-old Amschel Moses Rothschild, predates the family’s extreme wealth in banking and the still-flourishing conspiracy theories that success inspired.

Max Weinreich, one of YIVO’s co-founders, wrote a letter in 1932 to Forverts founding editor Ab Cahan, informing him of violent antisemitism, fomented by right-wing nationalists, on Polish universities. Its character is different, but in some ways similar to what a Forward editor may receive from a concerned parent or student today.

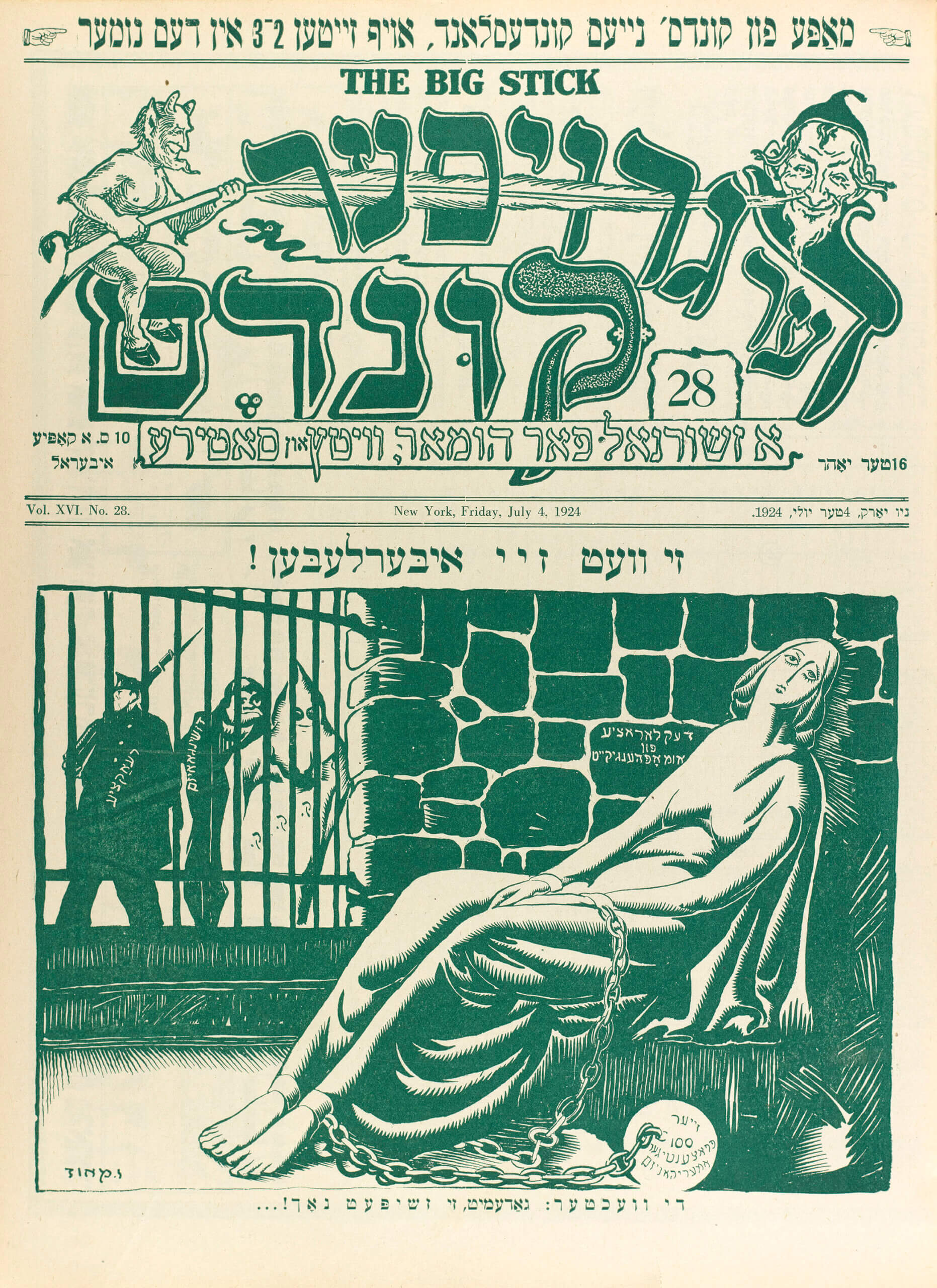

The national refugee service file on Otto Frank, denied immigration with Anne, Margot and Edith, despite a connection to the United States government through his friend Nathan Straus Jr., is chilling to see today. Jews were desperate to escape even before the war were met at the mercy of quotas. A political cartoon for the satirical paper Der groyser kundes, commenting on the immigrant predicament showed a woman embodying the Declaration of Independence behind bars, her jailers a klansman, a jingoist and a reactionary who lament “Goddamnit, she’s still breathing.”

The image is captioned, hopefully, “She Will Outlive Them!”

100 years after its establishment, YIVO now serves a community none in its founding generation could have anticipated when they began collecting folkways from shtetlach or even, in America, Yiddish translations of the U.S. Constitution.

And yet there is now uncertainty, division and a lack of consensus around what Jewish life should look like or where the future is heading. In 100 objects, the volume shows that this condition is nothing new, and while it may not be a guide to moving forward, it is proof that a people has endured before.