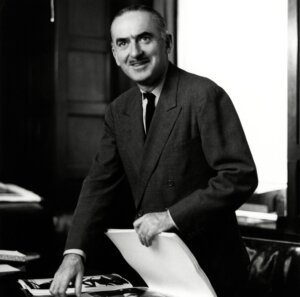

Si Newhouse with Anna Winotur at a book party in New York, 1990. Photo by Getty Images

Empire of the Elite: Inside Condé Nast, the Media Dynasty That Reshaped America

By Michael M. Grynbaum

Simon & Schuster, 368 pages, $30

If you were a top editor at Condé Nast Publications in the final decades of the 20th century, you could expect lavish perks: a no-interest loan to buy a house or apartment, a chauffeured town car, a five-figure clothing allowance and a virtually unlimited expense account.

And your writers did pretty well, too.

In his recent memoir, When the Going Was Good, Graydon Carter recounted his high-flying quarter century at the helm of Vanity Fair, when the magazine swelled with luxury ads, celebrity profiles and investigative coups. Even his admissions of failure read like boasts. Like the time, early in his tenure, that he inherited a story from Norman Mailer on the 1992 Democratic National Convention. Mailer didn’t do much reporting, and Carter considered the resulting article unpublishable. He nevertheless paid the full $50,000 fee (more than $114,000 in today’s dollars). Then he gave Mailer, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, another $50,000 not to write an assigned story on the Republican National Convention.

The hefty fees that Tina Brown pioneered at Vanity Fair, and that Carter and other Condé Nast editors also shelled out, went not just to literary stars like Mailer but to veteran journalists (most of whom did produce usable copy). And, in the 1980s and 1990s, before the Internet started devouring advertising revenue, they juiced the entire magazine industry. We scribes have since fallen on harder times. One former Vanity Fair contributing editor told me that his remuneration had shrunk by 90%, compelling him to abandon magazines for books.

Not surprisingly, a certain nostalgia infuses Michael M. Grynbaum’s brisk and engaging new cultural history, Empire of the Elite: Inside Condé Nast, the Media Dynasty That Reshaped America. It’s at once a celebration and a valedictory, witty without veering into (excessive) snark. The book reads as though Grynbaum, a media reporter for The New York Times, had fun writing it, even if he was born too late to enjoy Condé’s free-spending ways.

Long before the age of Internet influencers, Grynbaum argues, Condé Nast helped define the contours of gracious living. Magazines such as Vanity Fair, Vogue (under celebrity editor Anna Wintour), Architectural Digest, Gourmet, Bon Appétit, WIRED, GQ, Condé Nast Traveler, Condé Nast Portfolio, Allure, Self and others served as “merchants of fantasies” and arbiters of taste and style, dictating trends in fashion, food, design, travel and more. “At the peak of its powers,” Grynbaum writes, “Condé Nast cultivated a mystique that captivated tens of millions of subscribers across four continents, with brands that became international symbols of class and glamour.”

These days, he suggests, the company is “a husk of its former self,” with many of its publications either defunct or diminished. One notable exception is The New Yorker, the most intellectual of Condé Nast’s properties. Under longtime editor David Remnick, it has achieved profitability after years of losses, while winning 11 Pulitzer Prizes in the last decade (since magazines became eligible for the awards).

Grynbaum describes the two men who presided over Condé Nast in its heyday — Samuel I. “Si” Newhouse Jr., the company’s chairman, and Alexander Liberman, its editorial director — as “two Jewish outsiders with something to prove.” Newhouse’s grandfather, a Russian Jew, had changed the family name from Neuhaus. His father, Sam, owner of Advance Publications, purchased the Condé Nast magazines in 1959. Si’s brother, Donald, ran the Advance newspapers, where the real money was. Liberman’s family were Ukrainian Jewish refugees from the Russian Revolution. An “unrepentant aesthete and spendthrift,” Liberman was, according to Grynbaum, “the Rasputin to Si’s princeling.”

The duo’s hegemony evokes the clout of the Jewish moguls who founded the Hollywood studios in the early 20th-century, as Grynbaum notes. Men such as Sam Goldwyn, Louis B. Mayer and the four Warner brothers created cinematic fantasies that helped mold American culture. With magazines as their vehicle, Newhouse and Liberman managed a comparable feat, purveying an “inclusive kind of exclusivity.” The worlds of film celebrity and print came together annually in the Vanity Fair Oscar party that Graydon Carter, who “surfed the crest of Condé Nast decadence,” launched and hosted with brio.

Though the most powerful Newhouse relatives wouldn’t talk to Grynbaum, dozens of Condé employees, past and present, did. Empire of the Elite is filled with well-reported gossip and dish. Some of it — like the conflicting accounts of how Tina Brown moved, in 1992, from her successful editorship of Vanity Fair to The New Yorker and Carter ended up at Vanity Fair – are of interest mainly to magazine aficionados. Carter, who had a powerful ally in Vogue’s Wintour, says that Newhouse offered him his choice of the two publications, and he chose The New Yorker. But before he could assume the editorship, Brown (whom Grynbaum calls “a world-class self-promoter”) claimed it for herself. She tells a different story, alleging that Newhouse had been talking to her for years about editing The New Yorker.

The role of Condé Nast in the rise of Donald Trump is a tale with more contemporary ramifications. Grynbaum suggests that Trump was no more than “a provincial curiosity before GQ featured him on its cover” in a story by Carter, “and Si Newhouse personally dreamed up The Art of the Deal,” published by Random House, another Newhouse company. A key link between Newhouse and Trump was their friendship with the notorious New York lawyer and onetime Joseph McCarthy acolyte Roy Cohn; Grynbaum says the two men may well have met at a Cohn birthday party.

Grynbaum draws a straight line from The Art of the Deal to Trump’s starring turn on The Apprentice reality show, which in turn facilitated his improbable political career. Pamela Newhouse, Si’s daughter, talks to Grynbaum about the boost her father, who died in 2017 at 89, gave to Trump’s ambitions. “It is a source of deep regret to everybody,” she says. “But how would he have ever known?”

Julia M. Klein, the Forward’s contributing book critic, was a finalist for a Mirror Award for “Best single article, digital media” for a story in Condé Nast Portfolio. The Mirror Awards are administered by Syracuse University’s S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communication.