New York City mayor Eric Adams credits an unlikely source for helping him win the 2021 mayoral election: the Chabad Lubavitcher Rebbe, who died 30 years ago.

At a City Hall roundtable for Jewish journalists this week, Adams said that while he and Andrew Yang were fighting for votes in the Orthodox Jewish community, Deborah Halberstam, a Haredi Jewish woman in Crown Heights whose teenage son, Ari, was killed in an antisemitic terrorist attack in 1994, told Adams that she had a dream that the late Chabad Lubavitcher Rebbe urged him to visit the Ohel: the Rebbe’s resting place in Springfield Gardens, Queens.

“I did just that,” Adams told the journalists. “And as you know, we are standing here as Mayor Adams and not Mayor Yang.”

Adams has visited the Ohel six times — twice since being indicted on bribery charges in September. He’s not the first major politician to make a trek to the Rebbe’s resting site. President-elect Donald Trump visited the Ohel on the one year anniversary of Oct. 7. Last year, Argentinian President Javier Milei visited the Ohel shortly after winning the 2023 election.

But what is the Ohel, and why are powerful figures like Adams and Trump visiting?

What is the Ohel?

The Ohel, Hebrew for “tent,” is the resting place of Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe. He is buried in the Montefiore Cemetery in Queens, next to his father-in-law Yosef Schneerson, also a former Rebbe.

The gravesite sees approximately one million visitors a year, and it is the most visited religious site in Judaism outside of Israel, according to the Chabad Lubavitcher movement’s public relations manager Rabbi Motti Seligson.

The visitor’s center is open six days a week (it is closed on Shabbat) and 24 hours a day. While the Ohel’s visitor center doesn’t track exact numbers, Seligson said that the Ohel receives the most visitors in the spring, around the Rebbe’s birthday (11 Nissan on the Hebrew calendar) and the summer, around the date of the Rebbe’s passing, or yahrzeit (3 Tammuz). Major Jewish holidays like Rosh Hashanah also see an uptick of people coming to pray.

The gravesite of a tzaddik

To understand the significance of the Ohel, Seligson explained, one must first understand the importance of Schneerson, who is considered a tzaddik, or righteous person in Jewish tradition.

Schneerson was a leader in the Chabad Lubavitcher movement, a branch of Hasidic Jewry that originated in Russia over 250 years ago, which made its way to America in the 20th century. The movement’s philosophy was informed by the teachings of seven Rebbes, who expanded upon existing Jewish texts with their own mysticism and leadership.

Schneerson, a Ukrainian immigrant to New York during World War II, was the seventh and final Rebbe, appointed by his father-in-law in 1951. According to Schneerson’s biographer and former Forward editor Ezra Glinter, the Rebbe was revered. As stickers across Brooklyn and Israel can attest, some members of the Chabad Lubavitcher movement even saw the Rebbe as the Messiah.

During his life, Schneerson gave advice to thousands of people from the movement’s Crown Heights headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway. From Yitzhak Rabin to Bob Dylan, some of the world’s most influential leaders sought the Rebbe’s spiritual counsel. Schneerson advocated for the inclusion of prayer in public school education, according to Glinter, and after his death, the United States even established a day, April 9, in his honor as Education and Sharing Day.

When Schneerson passed away in 1994, his grave site in Queens became a popular pilgrimage point for people in the Chabad Lubavitcher movement as well as the broader Jewish community. The beauty of Schneerson’s teachings, Seligson emphasized, was the way Schneerson reached out to all Jews, regardless of denomination or level of observance.

Seligson added that while the Ohel is a relatively recent religious site, it is not a “novel” idea. Since Biblical times, Jews have made the gravesites of religious figures into holy pilgrimage sites, from the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron, to the Tomb of the Prophets in Jerusalem. “Jews have been doing this for the past 4,000 years,” Seligson said.

What does a typical visit to the Ohel look like?

On a rainy Monday afternoon in December, Jews from around the world huddled into a small building on the outer perimeter of the Montefiore Cemetery. People flowed in and out of the visitor center in raincoats, some rolling suitcases chatting in English, French and Hebrew.

A sign near the entrance advised men to put on yarmulkes and women to don modest clothing. At a cubby in the corner, visitors swapped out their street shoes for slippers. A 24-hour refreshment station in the corner offered apples, cookies and styrofoam cups of instant coffee.

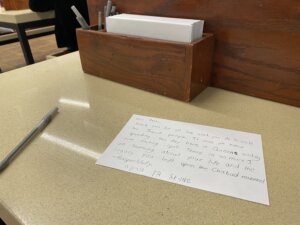

A group of Hasidic women in long skirts sat down along a row of desks beside men — some dressed in dress-pants and yarmulkes, others in sweatpants and toques — scribbling down prayers and requests, otherwise known as pidyonai nefeshot, on blank sheets of paper. Visitors folded their notes and walked through the center’s back door to pay their respects to the late religious leader.

Once outside in the cemetery, visitors can light a memorial candle on a shelf outside the grave. Then, they enter the Ohel itself, which has separate men’s and women’s entrances in the threshold leading to the grave room. Visitors stand while davening and then rip up their notes into the paper-lined pit surrounding the two tombstones.

Most visitors only spend a half-hour at the Ohel, but some people hang around at the visitor center much longer. Cindy Itzkowitz, 62, spent three and a half hours at the Ohel last Monday afternoon. A Long Island resident, she said she has come to visit the Ohel once a month for the past 20 years.

“It’s a special place to go to,” said Itzkowitz, who came to the Ohel to pray for her sister’s health.

Her favorite aspect of the Ohel was seeing visitors from far away, who often made the Ohel their first destination after landing at the airport. “From Paris, from Israel, from all over the world,” she said.

Other pilgrims were making the trip to the Ohel for the first time. Odelia Karo was visiting from Petah Tikva, Israel. She visited the Ohel for the first time with her brother, Nadir, on her 49th birthday. She wrote a note praying for her mother’s health.

Why do politicians and celebrities visit the Ohel?

According to Schneerson’s biographer Glinter, a trip to the Ohel can be both a way to improve community relations with and show respect for the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, as well as a way to honor the Rebbe’s teachings. Since the war in Gaza began, after Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7, a visit to the Ohel can sometimes also be seen as a symbolic way of showing support for Israel or global Jewry.

The Ohel has seen more visits from Israeli figures since Oct. 7. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s wife Sara Netanyahu – as well as freed Israeli hostage Noa Argamami, and several hostage families – all visited the Ohel earlier this year.

The Rebbe’s influence extends beyond the political and humanitarian spheres. Actor Michael Rappaport visited the Ohel in September. Long before the war, in 2019, British fashion model Naomi Campbell also visited the Ohel, and shared social media posts praising the Rebbe’s legacy.

“With so much discord and division across our society, the Rebbe’s words are more relevant than ever,” said Campbell. “Today, I rededicate myself to the Rebbe’s life-long mission of creating more light and goodness, and making a better future for ourselves and all of humanity.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO