Donald Trump delivers an address to the nation from the White House on June 21, 2025 about the three Iranian nuclear facilities that were struck by the U.S. military. Photo by Getty Images

The long days of suspense over the decision that President Donald Trump would make about American involvement in the Iran-Israel war have abruptly come to an end as B-2 bombers attacked three nuclear sites in Iran. But that earlier suspense now gives way to a suspense more diffuse and disturbing: Though the bombing mission has been completed, uncertainty and anxiety over its consequences has only just begun.

Has our government, displaying a confidence that may well be more hubristic than realistic, fallen into what is called the “Thucydides Trap?” Or is it instead what classicists would call a Thucydidean tragedy?

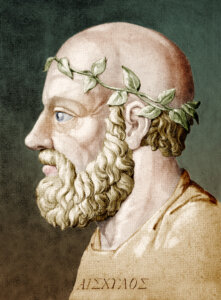

This Athenian writer has been portrayed by modern scholars as the father of objective history, exemplified by his account of the decades-long struggle between Athens and Sparta — a conflict that led to the decline and fall of both city-states — as a model of realism. Thucydides told it like it was, dramatizing Athens’ meteoric rise in the 5th century BCE from a backwater polis to a burgeoning power, one endowed with a navy that, seemingly overnight, seemed to threaten Sparta. Thucydides then deftly underscored the near-sudden fear that overtook Spartans, leading to their fateful decision to try and preempt the perceived Athenian danger.

Fast-forward two millennia to our own time and the political theorist Graham Allison, who introduced the notion of the “Thucydides Trap.” The ancient historian, Allison argued, provides a timeless rule — namely, that war is more likely than not when a rising power challenges an established power. Allison thus suggests the existence of apparently unchanging laws, first revealed by Thucydides that, like Newton’s laws for physical matter, govern relations between established and rising powers regardless of place and time.

While Allison had in mind the brewing tension between the United States and Communist China in the 1990s, observers have lately applied his model to the collision between Israel and Iran. The dominant military power in the Middle East, one credibly believed to have an atomic arsenal, is Israel. Yet it has grown increasingly anxious over Iran’s relentless pursuit of its own nuclear bomb. Moreover, given Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s unwavering vow to excise the “cancerous tumor” represented by the “Zionist regime,” Israeli anxiety is rightly existential, and a preemptive strike seemed justifiably rational.

That aerial strike, launched June 12, then widened to a series of targeted killings of Iranian scientists, government and military leaders, revealing that Israel’s goal is not just uprooting Iran’s nuclear facilities, but also the regime itself. In response, Iran hurled repeated salvoes of missile and drone attacks against Israel. Not only did these strikes and counterstrikes take the lives of hundreds of Israeli and Iranian civilians, but they also risked sparking a wider war — a vortex that risked pulling in the United States.

That is precisely what happened to President Trump. But behind his four-minute address to the nation that was Lincolnesque in its brevity and mere burlesque in its inanity, we can hear something else. It is dire and heavy, the sound of the grinding wheels of anagke, or necessity, and nemesis, or vengeance. As any ancient Greek historian or tragedian knew, these forces are as unstoppable as they are ineluctable. In the case of the 20-year war between Athens and Sparta, rational calculations proved as faulty as irrational forces proved overwhelming. Pericles, the Athenian leader praised for his ability to plan for all eventualities, died in the unanticipated plague that struck the city. The Athenian leader of the Melian expedition, who justified the destruction of Melos by claiming that might makes right, portended the destruction of the Athenian expedition to Sicily. And the list goes on and on.

The very same dreary process has been unfolding since last week. Benjamin Netanyahu took Donald Trump by surprise by ordering the air strike, Trump took his MAGA supporters by surprise by pirouetting to back an action he had adamantly opposed, Iran surprised more than a few military strategists by not backing down and instead doubling down.

And now Trump, perhaps surprising himself, has heaved our country into this fatal machinery. Rather than a trap, we are now inextricably entangled in a tragedy. Herein lies the lesson offered by Thucydides — a lesson found not in the study of international relations or military strategy, but instead in the study of human nature. In the end, Thucydides’ history does not instruct us on how to exploit or avoid certain situations, but instead instills the simple truth that, given our nature, there will always be situations we cannot avoid and, if we try to exploit, will have unintended consequences.

In his trilogy The Oresteia, the playwright Aeschylus, who fought in his share of wars, has the chorus chant that knowledge comes only with great suffering. That trilogy has since become a possession for all time. Brazenly, it seems, Thucydides makes the very same claim in the opening pages of his own work.

But is it brazen? Thucydides teaches us that far from being able to master events, events almost always master us. In other words, while events always change, human nature never does. Given the limited reach of reason and the unlimited reach of hubris, it could hardly be otherwise. If he were alive today, Thucydides would have reminded Donald Trump to open his eyes before he committed our country to war. We now know that Trump could not resist the temptation, thus adding yet another act to this tragic moment in our lives.