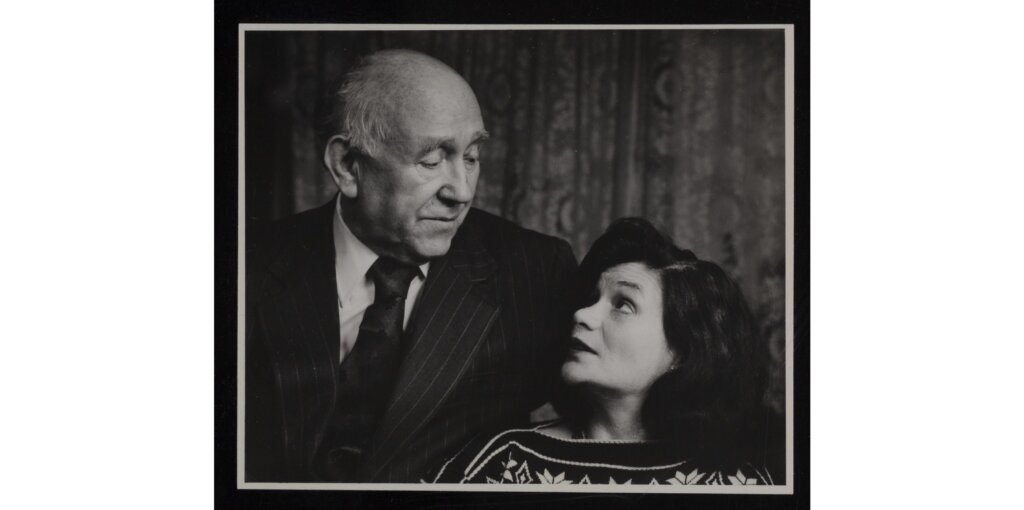

A portrait of Chaim Grade Image by Yehuda Blum

When millions of Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jews perished in the Holocaust, their stories, culture and way of life were wiped out with them.

One survivor, the novelist Chaim Grade, made it his life’s mission to keep their memory alive. In scores of stories, poems and novels, Grade faithfully recreated the world he lost in pre-war Europe. With his incredible memory, he vividly reimagined his formative years in Vilna and the yeshivas he attended.

After escaping the Nazis, Grade lived most of the remaining years of his life in the Amalgamated Houses in the Bronx. He lost his first wife during the war and remarried a fellow refugee, the intellectual Inna Hecker. With time she became his literary manager, translator and eventually the executor of his estate. To the dismay of scholars and researchers, though, the eccentric Hecker kept his Bronx apartment off limits to anyone.

Upon her death in 2010, scholars began clamoring for access to the apartment. Reminiscent of King Tut’s Tomb, Grade’s Bronx apartment contained some 18,000 books, scores of Yiddish manuscripts, galleys of typescripts, thousands of letters, boxes of newspaper clippings, photos, and more. But the primary goal for researchers was the hope that they would find an unpublished Grade novel.

The new English translation of his novel, Sons and Daughters, is the culmination of this search. The book, which was translated by Rose Waldman and published by Knopf, is set for release on March 25.

Originally called “Dos alte hoyz” (The Rabbi’s House), Sons and Daughters was serialized in the Yiddish newspaper Tog-Morgn Zhurnal between 1965 and ‘66, Waldman said. In 1968, Grade continued the novel in the same publication under a different title, “Zin un Tekhter” (Sons and Daughters) until August 1971. In 1973, after the Tog-Morgn Zhurnal ceased printing, he took the story over to the Forverts, switching the title once again, this time to Beys Harav, which means “the rabbi’s house” in Hebrew.

Following Grade’s death at the age of 72 in 1982, Hecker signed a contract with Knopf to have the novel translated into English for publication, but by 1983 she abandoned the effort. For almost 30 years, the project was at a standstill. With Hecker’s death, Grade’s literary estate was transferred to the YIVO Institute and the National Library of Israel. Since his widow’s obstruction was no longer an obstacle, Knopf was able to resume its quest to publish the novel, now renamed Sons and Daughters.

The narrative takes place in Poland on the eve of the Holocaust. At 649 pages, it is one of Grade’s longest novels. It masterfully describes the breakdown of tradition as modernity made ever deeper inroads into the shtetl way of life. The novel focuses on two rabbinic families, the Epsteins and Katzenellenbogens. In both families, the children are at odds with their parents’ religious way of life. One daughter goes off to nursing school in Vilna, a son becomes a Zionist and emigrates to Israel, and another son eventually flees to Switzerland and marries a non-Jewish woman.

One of Grade’s most disturbing characters is the mercurial Shabse-Shepsel. Ever an opportunist, he marries Draizel, the only daughter of a dealer in expensive fine china and crystal glassware. With her father’s passing, Draizel inherits the shop and all its fancy inventory. Although unsuited for the task, Shabse-Shepsel attempts to run the dinnerware shop. One day Meir Grosfatter, an eyeglass dealer and Torah reader, enters the shop looking for a gift for his daughter who has recently married. Concerned about the steep prices, Meir says he can’t afford to buy anything. But Shapse-Shepsel won’t take no for an answer. The narrator recounts Shapse-Shepsel’s train of thought:

“These products had been bought very cheaply before the war by his late father-in-law, the miser. So it would be a joy, an honor, and an advertisement for Shabse-Shepsel if these dishes graced the home of Meir’s only daughter. Meir could pay whenever he was able and however much he was able. And even if he never had the money, Shabse-Shepsel would forgive the debt entirely. He’d forget about this bit of glassware and crockery…He’d already forgotten! Shabse-Shepsel spoke as if gripped by a fever; his hands trembled. The way he begged made it seem as if he stood to lose both this world and the next if he couldn’t convince this man to take the dishes.” (page 216)

The fine china dinnerware seems to represent the fragile and precarious state of the Jews on the eve of the Holocaust. Shabse-Shepsel has a premonition that Polish Jewry is doomed. For this reason, he is willing and eager to forgo the debt. Nothing matters anymore. Shapse-Shepsel, seen as somewhat of a madmen by the other characters, has some of the most memorable lines in the novel. This is because initially no one believed the reports of the gas chambers and crematoria. Those escapees who tried to bring awareness of the death camps were considered crazy. Grade apparently created the character Shabse-Shepsel as a stand-in for the shtot meshugener, the town idiot. This narrative device makes the Holocaust palpable on every page of the first half of the book. And you truly feel it.

Grade was many things: a poet, a novelist, and a deep thinker who delved into the philosophical struggles of his time. However, all his literary output, some ten volumes of poetry as a member of the Yung Vilna group and ten volumes of prose written after the Holocaust, circle back to his conflicted childhood and early yeshiva education.

Grade’s father, Shloyme-Mordkhe, was a maskil, an adherent of the Jewish Enlightenment, who wanted Grade to receive both a Torah education and secular knowledge. But his mother, Vella, was a pious woman who insisted on sending young Chaim to the extreme Novardok mussar yeshiva. Despite Grade’s eventual disaffection with the Orthodox lifestyle, he never managed to free himself from its hold on his psyche. For the rest of his life, he grappled with questions that were implanted within him during his formative yeshiva years: What is morality? Can one be truly moral without Torah? How does one reconcile the ancient, revealed truth of the Torah, with the modern world and its scientific advances?

As a yeshiva student, Grade was trained in the art of Talmudic debates. Unlike the first half of Sons and Daughters, which describes the difficult social reality of Polish Jewry on the eve of the Holocaust, the second half of the novel is predominantly philosophical. It is in the lengthy and engaging philosophical debates that Grade truly shines.

The second half focuses on Naftali Hertz Katzenellenbogen, the rabbi’s son who relocates to Switzerland to escape the overbearing religious strictures of his esteemed father. He studies philosophy at the university, marries a gentile woman and has a son.

Toward the end of the book, Grade introduces the character Khlavneh, a young Yiddish writer, apparently modeled on himself. Khlavneh strenuously insists that secular Yiddishists like himself hadn’t really rejected the Jewish tradition. Rather, they understand religion and Jewish folklife differently than their predecessors. Khlavneh sums up his belief system with the following words:

“Just as the eyes are the liveliest part of the face, and Shabbos is the crowning day of the week, it’s the legends that have captivated the Jewish heart more than the laws themselves. The history of the patriarchs in the Chumash and the tannaim in the Talmud, the allegorical passages about Elijah the Prophet and the stories of the lamed-vovniks, the stories about Jews who’d martyred themselves for the sanctification of God’s name — in these lie the charm and magic, and these are what breathed life into Jewish laws.” (page 598)

The lamed-vovniks refer to the legendary 36 righteous people whose identity, according to Jewish mysticism, is hidden to everyone, even to themselves.

On the eve of the Holocaust, millions of Eastern European Jews shared this belief. They read the numerous daily and weekly Yiddish newspapers voraciously. They devoured the Yiddish novels and poetry that was produced by Grade and his friends in Yung Vilna. It’s very possible that even Jews in the concentration camps dreamed of being rescued by one of the lamed-vovniks. And to this day, Khlavneh’s creed resonates even with Orthodox Jews.

On a historical note, it may be possible to identify characters in the novel with people who actually crossed paths with Grade before the war. Yehuda DovBer Zirkind, a Yiddish literature researcher at Tel Aviv University, is writing a dissertation about Grade’s work where he links the character Khlavneh Yeshuron, the suitor of the rabbi’s daughter Bluma Rivtche, to Grade himself. Bluma Rivtche in turn is based on Grade’s first wife, Fruma Lieba, who perished in the Holocaust.

The character Naftali Hertz, a philosophy student, seems to be based on the deeply conflicted scholar Jacob Klatzkin, who himself fled his Orthodox upbringing and married out of the faith. Like the real-life Klatzkin, Grade’s Naftali Hertz can never fully free himself from his intense Orthodox upbringing.

Grade’s original audience for the Yiddish serialized version was a previous generation of Yiddish readers. Now that the book is available in this superb translation by Rose Waldman, it can appeal to a new and universal audience. For those who would like a vivid picture of pre-war Jewish life in Europe; who appreciate a brilliant recreation of generational conflict in Jewish families, or who may be struggling with their own questions of faith, Grade’s novel may truly resonate.

Though the Holocaust itself is never mentioned in the book, it is felt on every page. In some sense, Sons and Daughters can be considered a Holocaust memorial, as the events it describes foreshadow the upcoming annihilation of Polish Jewry. It is this tragic awareness that animates Grade’s questioning and demand for answers from the rabbinic establishment, from the Torah, and from God himself.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO