Jeanne Golan has recorded three albums of music by persecuted composers, including a double CD of Viktor Ullman’s sonatas. Photo by Jon Kalish

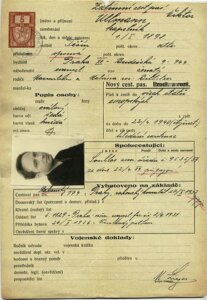

For the last 15 years, New York pianist Jeanne Golan has been recording and performing the works of composers persecuted by the Nazis as part of what has come to be known as the recovered voices movement. It began when Daniel Rothman, a composer friend in Los Angeles, suggested she check out the piano sonatas of Viktor Ullmann, who was held in the concentration camp in Terezin, Czechoslovakia. Ullmann was sent to Auschwitz where he perished in October 1944. Rothman thought the Czech composer’s seven sonatas might speak to Golan.

They did. In the ensuing years, the pianist has recorded three albums of music by persecuted composers, including a double CD of the Ullman sonatas.

As part of her deep dive into Ullmann’s life, Golan traveled to Europe and met with two survivors of Terezin, which is located about 40 miles north of Prague. Between 1941 and 1945, Terezin served as a ghetto-labor camp and a transit camp for Czech Jews who were deported to killing centers, concentration camps, and forced-labor camps. The Third Reich used Terezin for propaganda, claiming that it was a spa town, and Nazis staged social and cultural events there for visiting dignitaries and the Red Cross. Of the approximately 140,000 Jews transferred to Terezin, nearly 90,000 were deported to points further east and almost certain death. Roughly 33,000 died in the camp itself.

One of the survivors Golan met with was a 106-year-old musician named Alice Herz-Sommer, who studied at the conservatory in Vienna with Ullmann. Herz-Sommer premiered Ullmann’s Sonata No. 2 and dedicated his fourth Sonata to her.

“I asked her about practicing [at Terezin] and she said they would work out the fingerings on an imaginary keyboard because you couldn’t really practice [at the camp],” Golan told me.

Golan could relate to the imaginary keyboard because it was a technique she had employed before she had a piano in her Manhattan apartment.

A prolific output

When I spoke with Golan, she was preparing for a Yom HaShoah concert at the Manhattan social services agency DOROT, featuring the work or Mieczyslaw Weinberg, a Polish composer who fled to the Soviet Union, and Walter Kaufmann, a Czech composer who fled to India, as well as popular songs sung by Ukrainians in the Red Army.

Golan describes the Weinberg sonatina she is playing as “full of little devilish moments and a jangly kind of waltz.”

One of the reasons she connected with Weinberg’s work, she said, is that he drew on elements of Yiddish folk music, which were very much a part of her upbringing in Natick, Mass. Weinberg grew up in the Yiddish theater in Warsaw, which he fled in 1939 after the Nazis started bombing the city. His family perished in Auschwitz.

As a refugee, Weinberg sent a score to Dmitri Shostakovich who realized how talented the young Polish composer was and took him under his wing. Weinberg was hit with a trumped-up murder charge and taken to Siberia where he spent a few months on death row until Stalin died. After his release, Weinberg continued his prolific output, composing 22 symphonies, several operas and many pieces commemorating the Holocaust.

“He wrote an awful lot of terrific music,” said Simon Wynberg, artistic director of the ARC Ensemble, a chamber music group in residence at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto. Since 2002, the ensemble has been recording and performing music suppressed and marginalized under the 20th century’s repressive regimes, mostly the Nazis.

“Somehow his value had not really [been recognized outside] the Soviet Union,” Wynberg said. “As soon as people started to hear his music, it was a bit of a tsunami.”

The ARC Ensemble has also recorded the work of Walter Kaufman, one of the composers Golan will be performing at her Yom HaShoah concert.

“They’re enchanting,” Golan said of Kaufman’s works. “They’re like pre-minimalism.”

Kaufman turned down his doctorate at Prague’s conservatory because his faculty advisor was a Nazi sympathizer.

“He just couldn’t abide it,” Golan told me. “So, he didn’t get his degree after finishing it and then got out of town.”

Kaufman made his way to India where he eventually landed a job as music director at All India Radio before heading to North America where he served as the first music director of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. He wound up at Indiana University, where, despite his lack of an official doctorate, he was hired as a professor of musicology and published research on Indian music.

“Kaufman was a great scholar of Hindustani music,” said Brett Werb, the music curator at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. “I studied Hindustani music when I was in graduate school [at UCLA] and we used his books.”

Salavaging music

Not all of the key figures in the recovered voice movement are Jewish.

An amateur Polish musician named Aleksander Kulisiewicz was held at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp north of Berlin. Kulisiewicz became a guardian of music and poetry from the camps. After the war, Kulisiewicz returned to Poland and assembled an archive of camp music, which he went on to perform in more than a dozen countries. He dedicated the remainder of his life to sharing the music. The Aleksander Kulisiewicz Collection is probably the largest collection of songs from the camps at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, according to Werb.

The Italian composer and musicologist Francesco Lotoro, who converted to Judaism, has been working since 1990 to bring recovered voices to the world’s attention. He created an archive of 8,000 music scores written in concentration camps and is credited with disseminating the work of Polish violinist and composer Jozef Kropinski, who was one of the most prolific concentration camp composers. Working by candlelight, Kropinski secretly wrote more than 400 works — waltzes, quartets, songs, tangos, and an opera.

A 60 Minutes segment on Lotoro moved Janie Press, a retired fashion industry executive-turned-cabaret singer, to create Holocaust Music Lost & Found, which has produced 11 recovered voices concerts, mostly in New York. Among its upcoming events is a presentation on Sing, Memory, a new book about Kulisiewicz.

“Salvaging music is no less important than recovering the looted art treasures that were found in a cave at the end of World War II,” James Conlon, a towering figure in the recovered voices movement who now serves as the music director of Los Angeles Opera, once said.

A production of Ullman’s opera Der Kaiser von Atlantis, conceived by Conlon, has traveled extensively. A biting critique of totalitarianism and the dehumanizing effects of absolute power, the opera mocks the futility and horror of war. The character of the emperor has been widely interpreted as a stand-in for Hitler. The Nazis halted production after a dress rehearsal at Terezin and the opera didn’t premiere until 1975 in Amsterdam.

“That was the opera that put the Nazis on to him, that he was really writing subversive music while he was in Terezin,” Golan noted. “Once that opera was seen, he was put on the death list.”

Widening the circle

Wynberg of the ARC Ensemble told me he doesn’t bring a lot of sentiment to his recovered voices work.

“The nature of their lives is interesting after the fact, but the most important thing is [whether] this music is worth our time and is it worth reviving,” said Wynberg. “And fortunately, all these guys that we’ve been looking at were incredibly gifted.”

Werb of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum said he continues to be surprised that new music keeps turning up.

“I don’t mean huge caches of undiscovered masterpieces, but a song here or there that’s never been written down or published or otherwise explored or studied,” he said.

This includes what Werb described as “a gargantuan collection” from Ukraine assembled by the great Soviet Jewish folklorist Moisei Beregovsky, who interviewed Jewish refugees with a cylinder recorder after liberation. Beregovsky was sent to the Gulag and died not knowing what happened to his material. Sometime in the early 1990s, it started to come to light and took 20 years to digitize. The project was finished just before Russian shells started to fall on Kyiv.

The recovered voice movement will no doubt also mine the Lithuanian state archive, which has been digitized and provided to YIVO. That collection holds music scores by Jewish composers who were confined to ghettos in Vilna and Kovno during the Nazi occupation.

For her part, Golan is looking into the work of Italian composers. She’ll be doing three concerts for DOROT next year, she says, and vows to fold in one or two new pieces of music in each one of them.

“I just want to keep widening the circle in many ways,” she told me. “I’ve learned that you throw a pebble in the pond and it ripples out and you just don’t know what you’re going to encounter. I love that.”

You can stream Jeanne Golan’s Dorot concert here or register for Holocaust Music Lost & Found’s May 7 book presentation and performance at Hebrew Union College here.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO