Treasure discovered during a 1968 dive. Courtesy of Howard Rosenstein

It all started with one gold coin.

That’s how Howard Rosenstein’s career as a scuba diver, entrepreneur, explorer and raconteur began. It was August, 1968 and Rosenstein, a long-haired surfer kid of 19, had come to Israel from Los Angeles to attend college and study anthropology and archeology in Tel Aviv. He’d done some skin diving in the United States and was snorkeling in the Mediterranean.

Two years later, he dove down eight feet, saw something flicker on the ocean floor and scooped it up. It was a coin that read IMP.CAES on its edge. It turned out to be a Roman coin from the time of the Emperor Trajan (98-117 CE). And it had value.

It was the first of many coins — “hundreds” said Rosenstein — that he found, then sold to dealers. He’d come to Israel with $500 and now, “I was starting to see money for the first time in my life. That was like real money,” he told me.

The money allowed Rosenstein, who was learning Hebrew, to build a new industry: dive centers, first in the Mediterranean and then in Sharm El-Sheikh on the Sinai Peninsula. Over the years, Rosenstein became a pioneer of recreational diving in the Red Sea.

[embedded content]

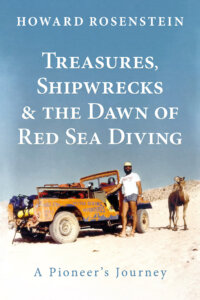

Rosenstein started writing the recently-published memoir of his early years, Treasures, Shipwrecks, and the Dawn of Red Sea Diving: A Pioneer’s Journey, during the COVID-19 lockdown.

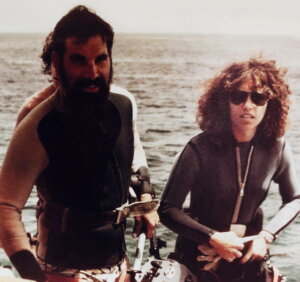

“All of a sudden we had time on our hands,” Rosenstein told me over Zoom from Costa Rica where he was attending a conference. Over the years, he had kept numerous notebooks and had been a “lunatic photographer.” His wife and dive partner, Sharon, had “saved every article that was ever written about us, every magazine, newspaper story. We had videos of TV interviews. So there was a lot of material that had to be just waded through.”

The book is about the many pleasures of scuba diving, of the shared camaraderie, of shipwreck discoveries. As well as time spent with diving enthusiast Leonard Bernstein, close encounters with aquatic creatures and, of course, ever-lurking danger in the deep.

It’s also a story about the Middle East at a time when there was strife, yes, but also hope for peace.

“There’s certain themes or maybe messages that are in the book,” Rosenstein said. “One of them has to do with the challenges of the times, of seizing opportunities. One very important theme for me is that I was part of a process that transformed a historic battleground, which Sinai has been from time immemorial, from the time of the ancient Egyptians and the Mesopotamian rulers, into an international playground, a desired tourism destination.”

Rosenstein’s initial diving pursuits came in the wake of 1967’s Six Day War and continued through the Yom Kippur War in 1973. While the aim was to build a successful business, that wasn’t the sole aim; he also wanted to show that a place could be changed “from a war zone to a travel destination.”

“We fought very hard for environmental protection,” he said. “So, there was no coral collecting or fishing and commercial fishing. We protected the sharks. And then there were no pollutants going into the sea. So those two themes of going from war to peace and avoiding exploitation by protecting the beautiful environment, were two great goals and achievement.”

There was another important component to Rosenstein’s journey. “I really wanted to become part of the Israeli society,” he said, “and it’s not easy being an immigrant in every culture. This allowed me to get on a ground floor of being the so-called expert, which I really wasn’t at the time, and a brand-new industry, a brand-new branch of tourism. So, there was an acceptance factor.”

There was also a lot of fun to be had – and a bit of chicanery. In 1977, the shipwreck adventure movie The Deep, starring Nick Nolte, Robert Shaw and Jacqueline Bissett, became a hit. “That did a lot to generate interest in shipwreck diving, which is an exciting niche of scuba diving,” Rosenstein said. Many tourists became scuba diving enthusiasts and they yearned to explore shipwrecks. Problem was, for Rosenstein and his team, which included his wife: They hadn’t found a shipwreck yet in the area.

“We were young entrepreneurs, and it was similar to the Wild West, where you had to do a lot of things to survive and to get on,” said Rosenstein. “We were always thinking about different ways of getting business. All of a sudden, people wanted to go dive on a wreck. We were sitting at the end of the world in a beautiful, pristine place, but we didn’t have that component yet.

“So, a bunch of us were sitting around, friends and colleagues, and we’re saying, ‘What are we going to do? We don’t have a wreck, and we need a wreck.’ One of us could construe a plot so there was a wreck. We could contrive an entire story without having the wreck yet. And we would kind of give off little tidbits to the visiting travel agents or divers who would be coming into the area, influencers, as they’re called today. They would say, ‘Well, take us there; we want to see it.’ We said, ‘Well, it’s not available right now. It’s a security area.’”

There were other ship skeletons sitting on the reef, but they were rusted and rotting away. And then some Bedouin fishermen told him about a nearby wreck. They explored the area and found what turned out to be a British ship, the S.S. Dunraven, which hit a reef and sank in 1876 en route from Bombay to Liverpool. “It was the first wreck that had ever been a diveable wreck,” Rosenstein said. “So, all of a sudden, we had a ship that can match the story that we had construed.”

Rosenstein met Leonard Bernstein, who was a scuba diving enthusiast, through a Bedouin friend who said that the conductor was in town. Rosenstein left a note at Bernstein’s hotel: “I’d be honored if you would come to the diving center tomorrow, and I would take you out to a very nice place to go diving.”

“And sure enough, the next day he showed up,” Rosenstein said.

They got along famously, on sea or on land. The maestro, who first conducted in Israel during the War of Independence in 1948, invited Rosenstein and his wife out to dinner. “And then we made a reciprocal invitation for him to come to dinner at our house the next night and he came back several times.”

Then, at a latter point, there came a private birthday concert.

Bernstein was in Tel Aviv conducting the Israeli Philharmonic and invited Rosenstein to see the performance and then inquired if they might go sailing the next day. A National Geographic team was going to take photos aboard the ship. Alas, the sail had to be scrapped because of inclement weather.

“We were just sitting there on the beach,” said Rosenstein, “all of us together and saying, ‘What are we going to do? We can’t go out on the boat.’ And one of the Geographic guys said, ‘Well, anyway, Howard, happy birthday.’”

“What! It’s your birthday?” Bernstein exclaimed. “OK, let’s go up to my suite. We’re going to celebrate.” He had been staying in the penthouse at the Tel Aviv Hilton, appropriately furnished with a Steinway piano.

On the way up, Bernstein stopped by the reception desk and ordered champagne and a birthday cake. “And then,” said Rosenstein, “he entertained us. He said, ‘What do you want me to play?’ I was thinking of something smart like Rachmaninoff or something like that, but I said, ‘West Side Story — I love that.’ So, he did a medley.

“Then, after that, he said ‘Anything else?’ I said, ‘I want to hear the old Yiddish music.’ And he broke into this medley with ‘Yidl Mitn Fidl,’ which was a popular Yiddish song in the ‘30s or ‘40s. It was hilarious. A totally bizarre situation, but fun. He’s extremely theatrical. He wanted to give me a birthday kiss and he really did. And my friend from National Geographic shouted, ‘No tongues!’”

With the Camp David Accords, signed in 1979 between Israel and Egypt, Rosenstein had to give up his home and business. but he said, “We walked out of the Sinai in 1982 with our heads held high, making a real contribution and compromise. We gave up everything for peace. We really did. We supported it — myself, my family, and many in the community — even though we lost much. And that’s because we were looking out for the future of our kids.”

Later, Rosenstein founded Fantasea Cruises, which rented out a luxurious yacht for diving expeditions, but was forced to sell in 1997 because “the Egyptians banned foreign flag operations.” He then founded an underwater photo equipment company called Fantasia Line in 2002, and after turning over the CEO reins to his son Nadav he now considers himself retired.

So, at 77, is diving as much of fun for him now as it was when he was young?

“That’s a good question,” Rosenstein said. “I still get excited about diving. I mean, at any given dive, you can see something that you never saw before. And the Red Sea is probably one of the most beautiful areas of the world that you can dive. You can find anything at any time. I’m talking about marine life. The Red Sea has been very good to me, it’s true. You can find a shipwreck, or in my case [in the Mediterranean] I’ll find a gold coin or a treasure.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO