The New York City Dyke March has come close to dissolution over its stance on Zionism. Photo-illustration by Nora Berman/Getty Images/Instagram

Jodi Kreines, an organizer for the 2025 New York City Dyke March, was concerned. It was mid-March; in barely three months, between 15,000 and 30,000 self-identified dykes would converge in Manhattan for the annual march, which explicitly centers queer women. But no logistics work had begun.

Kreines, who is Jewish, was standing in the way — by refusing to sign off on an Instagram statement explicitly defining the Dyke March as anti-Zionist.

But her fellow organizing committee members were insistent, and Kreines finally gave in, afraid, she said, of “putting the entire march in peril.” On March 14, the march’s official Instagram account posted that they were “strengthening their commitment to anti-Zionist, anti-racist, pro-LGBTQ+ community standards.”

For a significant number of Jewish and Israeli dykes who have long been involved in the march, it was a moment of rupture. Pro-Palestinian supporters also objected, arguing the organization has not gone far enough.

“I feel too queer for Jewish spaces, but I also feel too Jewish for queer spaces.”

The march — which takes place without permits, corporate sponsorship or police protection — has come close to disintegration over its new, explicitly anti-Zionist stance. In doing so, it has become a microcosm of the colossal division in progressive politics over Israel, Palestine and antisemitism. That shift has been particularly painful for queer Jews, who have increasingly encountered litmus tests in LGBTQ+ spaces over Israel and Palestine amid the Israel-Hamas war.

For some of those caught up in the Dyke March drama, it was evidence that a space that was once a refuge was now the opposite. “I feel too queer for Jewish spaces,” Kreines said, after the statement went out, “but I also feel too Jewish for queer spaces.”

In the best of times, the Dyke March is an outburst of ecstatic presence: queer people expressing joy, rage and strength in their identity. Now is not the best of times — for the Dyke March, or for Jews navigating complicated questions of identity within progressive movements at large. As Jewish former committee member Nate Shalev told me, “This is both about the Dyke March and not about the Dyke March.”

A standoff over Jewish pride

NYCDM organizers largely trace the beginning of conflict over the march’s stance on Zionism to the 2017 Chicago Dyke March, when Jewish dykes carrying rainbow flags bearing a white Magen David — traditionally viewed as a symbol of Jewish LGBTQ+ pride, and not related to the state of Israel — were asked to leave because the flag’s resemblance to the Israeli flag “made people feel unsafe.”

New York City organizers, I learned through interviews with several current and former members of the organizing committee, debated whether they should ban national flags in response. (The Dyke Marches operate independently from each other; following the Chicago incident, the Chicago and Washington, D.C., Dyke Marches banned “nationalist symbols,” although the D.C. March later agreed to permit Jewish pride flags.)

“Every single year we had this conversation,” Shalev, who spent 10 years on the NYCDM organizing committee, from 2013 to 2023, told me. “And every single year we came back to inclusion: Israel means a lot of different things to many Jews, and by banning this symbol, by banning the Star of David, you’re going to exclude a lot of Jews.”

Inclusiveness had, intentionally, been a core value of the march from its earliest days. “There was a lot of fine-tuning how political the march could be,” Valarie Walker, an original member of the New York City Lesbian Avengers — a group of activists that founded the Dyke March — told me of the march’s founding. “You realized that the more specific the message, the more dykes were excluded, and that was just not what this was about.”

Everything changed on Oct. 7, 2023.

What does ‘Zionism’ mean?

At the time of the Hamas attack, the NYCDM organizing committee was in their off-season: There is regularly a long break in activity after the march, each June, until the start of planning for the next one, in the following January or February. So the organization made no public statements acknowledging the terror attack, or Israel’s subsequent war in Gaza.

Behind the scenes, however, there was fierce debate. Multiple Jewish dykes who ended up leaving the organizing committee after Oct. 7 told me that they didn’t object to NYCDM supporting Palestinian self-determination. But they also didn’t feel that their perspectives and lived experiences with Zionism were valued.

“Whatever I was going to say didn’t actually matter,” Shalev said of these discussions, “because they felt really confident in their understanding of what the truth was.”

“And that really doesn’t happen in how we think about other identities, how we respect and value each other in queer communities.”

The vast majority of American Jews identify as Zionists, Jewish dykes explained, with Zionism meaning different things to each of them. Yet Jewish dykes would get pushback from other committee members, most of whom, according to interviews, were white, from Christian backgrounds.

The committee’s non-Jewish members seemed to only be able to equate Zionism with its most extremist version, as expressed by far-right Israeli ministers like Itamar Ben-Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich. Plus, because there were anti-Zionist Jews, the counterargument went, a decision to explicitly endorse anti-Zionism would not inherently affect Jews as a group — just the Zionist ones.

Finally on April 1, 2024, the NYCDM posted on Instagram to affirm their “stance for liberation, including for the liberation of the people of Palestine.” The post also condemned “the manipulative use of Jewish and queer identities to justify violence.”

‘Dykes against Genocide’

By May 29, the Dyke March had announced their 2024 theme: “Dykes Against Genocide.” Within Our Lifetime, a controversial pro-Palestinian and anti-Zionist activist group that praised the Oct. 7 attack, was among the five groups for whom that year’s march would raise funds.

Some Lesbian Avengers, like Walker, were increasingly concerned that the NYCDM was abandoning its apolitical roots. In their minds, being a dyke at the Dyke March was the political stance; the day was supposed to stay focused on that single, strong statement.

But the COVID-19 pandemic had changed the way people participated in the Dyke March’s non-hierarchical decision-making structure, with broad implications for how the organization at large made choices about its political priorities.

Organizing previously conducted in person or by phone moved online to Slack, a platform some older dykes found challenging to use. And without a formal leadership in place, on Slack, a new member who started engaging the week before the march had as much power as an organizer who had been doing it for years. Current committee members told me that between 80 and 100 people were in the committee’s Slack to plan the 2024 march, but fewer than a third of them were actively involved in planning the event. The loudest voices online — typically, according to my interviews, the youngest members — ended up having the most sway.

In the final weeks before the march, tensions escalated. Then, on June 18 — 11 days before the march — Maxine Wolfe, one of the march’s founders and a legendary queer activist with ACT UP, wrote in an email to the organizing committee that she would not attend the march in the future “if the goal remains creating a committee and subsequently a march that adheres to one political program.”

Wolfe, who is Jewish, wrote that she knew many Jews who would not be joining the march, and that she felt the march had strayed from its founding values. She hoped that the march would change course and remain an inclusive space, she wrote: “We did not create the Dyke March to be a sectarian left grouping which is what it is fast becoming in my view.”

The first response to Wolfe from a committee member was swift and brutal: “Good riddance and pls understand how replying to a CC/BCC list works.” It was signed “a bipoc dyke who doesn’t support genocide and will be attending w many of her Jewish anti Zionist dyke friends.”

Are Jewish dykes ‘safe and welcome’?

The fallout over Wolfe’s letter put more pressure on a new subcommittee working to respond to Jewish dykes’ concerns before the march. I reviewed hundreds of Slack communications from the subcommittee’s conversations, as well as private Instagram messages sent to the NYCDM account, and internal emails.

It was clear that the overwhelming majority of the subcommittee identified as anti-Zionist and pro-Palestinian, but also felt residual guilt over ignoring Jewish and Israeli suffering.

“I have genuinely wondered if this is an organization I can be a part of if we can’t say genocide is wrong and so were the October 7th attacks,” one sub-committee member wrote on their internal Slack channel.

Another responded that the NYCDM needed “to acknowledge the grief and loss in the Jewish community.”

“I am certainly not a Zionist,” they hastily clarified, but “it has been so grating to hear any semblance of compassion” for Oct. 7 victims “equated with diminished compassion for Gaza and Palestinians.”

The subcommittee, which had been working on the issue for months, felt that it was urgent. Yet the larger organizing committee largely failed to respond to requests for feedback. Meanwhile, the NYCDM continued to be inundated with direct messages asking if Jewish and Israeli dykes were welcome.

Late in the evening of June 27, just two days before the march, the subcommittee posted a final draft of a statement about Jewish inclusion in the march on Slack. It was approved by a simple majority of the online subcommittee members, and shared on the march’s Instagram.

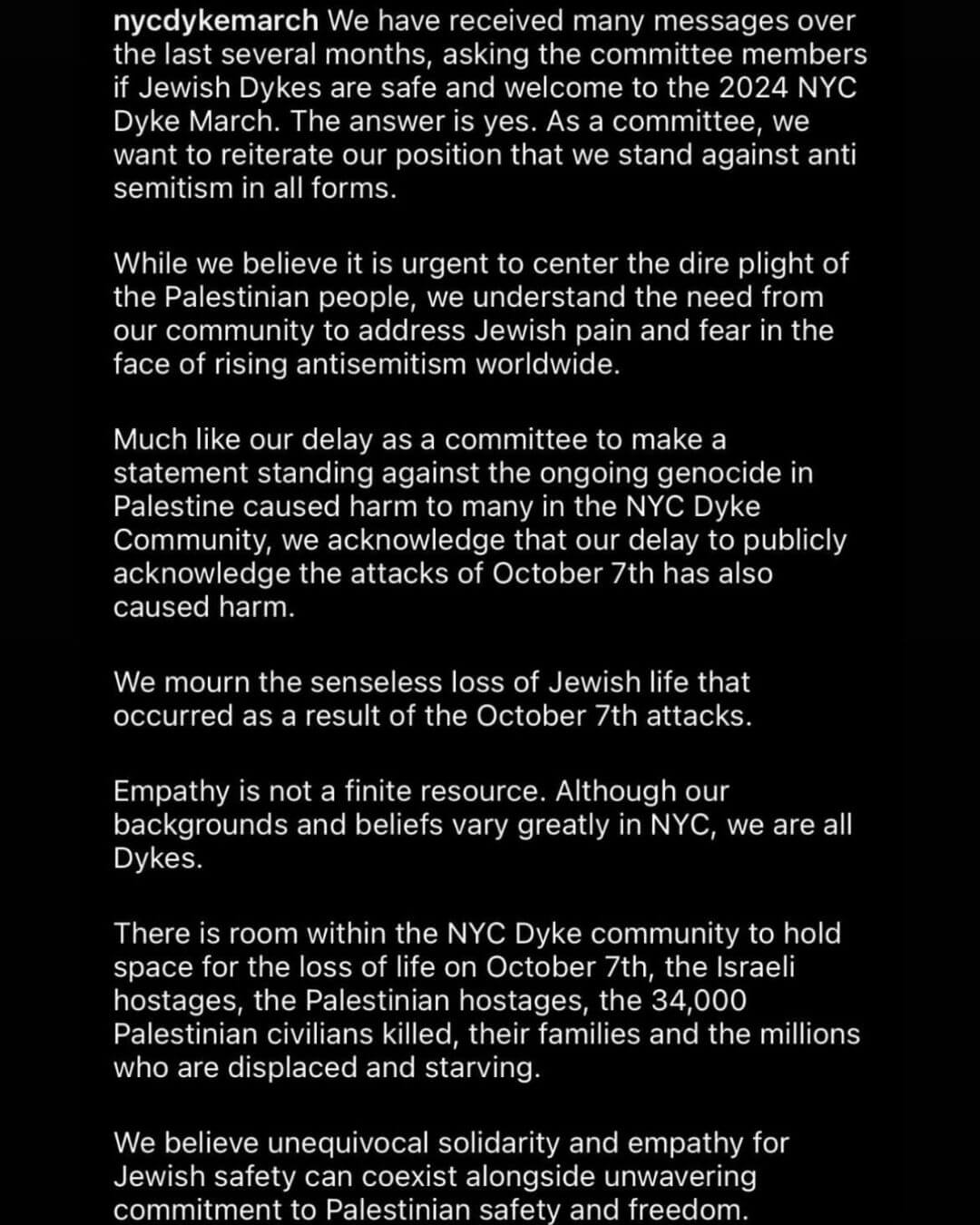

“We have received many messages over the last several months, asking the committee members if Jewish Dykes are safe and welcome to the 2024 NYC Dyke March,” the statement read. “The answer is yes. As a committee, we want to reiterate our position that we stand against antisemitism in all forms.”

The March needed to “center the dire plight of the Palestinian people,” it continued, but also “address Jewish pain and fear in the face of rising antisemitism worldwide.” The march’s failure to issue a statement either about the “ongoing genocide in Palestine” or the Oct. 7 attack had “caused harm,” it acknowledged.

“Empathy is not a finite resource. There is room within the NYC Dyke community to hold space for the loss of life on October 7th, the Israeli hostages, the Palestinian hostages, the 34,000 Palestinian civilians killed, their families, and the millions who are displaced and starving,” it concluded.

“We believe unequivocal solidarity and empathy for Jewish safety can coexist alongside unwavering commitment to Palestinian safety and freedom.”

As soon as the post went live, some committee members who had been inactive for months logged on to Slack, outraged. They expressed frustration that the entire organizing committee had not been able to vote on it, even though the subcommittee had been soliciting input for months.

Within 30 minutes, the post was deleted.

I asked four members of the 2025 organizing committee why the original statement had been removed. “Some members, BIPOC or non-BIPOC, found the language placating,” D., a member of the committee who requested to remain anonymous due to concerns over their immigration status, said.

They explained that a message expressing that Jewish dykes were welcome at the march would have been fine, but that committee members felt that mentioning Oct. 7 would be construed as “too explicitly political,” as the attack was often used as justification for Israel’s war.

‘The post was a mistake’

The next day, a new, much longer statement went up that disavowed many of the points made by its predecessor. It claimed that the decision to make the original post had been the work of a rogue single member, adding that it did “not reflect the official stance of the Dyke March.”

The NYCDM recognized “the immense harm caused when we backtracked on our unapologetic stance against Zionism by conflating anti-Zionism with antisemitism,” the statement read, and that “any language we put out which is not clearly opposed to a Zionist, imperialist agenda is harmful to all.”

The uproar was instantaneous. Many Jewish dykes felt betrayed. If the march wasn’t “able to post about a terrorist attack on October 7th without receiving backlash from your community,” one wrote, “maybe you should think about the community you are representing.”

“If enough people send DMs on Instagram expressing outrage, they will change course entirely.”

Another commented: “As a Jewish dyke this is so so painful. You literally retracted a statement that said ‘empathy is not a finite resource.’ I guess for y’all it is.”

The pro-Palestinian camp appeared to be just as angry: one commenter wrote, “This whole thing reeks of Zios tryna cover their ass.”

The comment thread quickly devolved into antisemitism and conspiracy theories, including, at one point, allegations that Israel had been responsible for the Sept. 11 terror attacks. Some commenters also spread disinformation about the Oct. 7 attack.

The Instagram conversation quickly turned to outing the alleged “Zionist” authors of the original post. Within 24 hours, the committee member who had posted the original Instagram statement was doxxed. It is unclear who specifically was responsible for the doxxing, but current and former NYCDM organizers all confirmed that it was a fellow committee member.

The doxxed individual, who requested to speak anonymously out of concern for their own safety, received threatening messages on social media and had to remove their business from Google. In screenshots of the Instagram live feed of the 2024 NYCDM, which I independently reviewed, their name and physical address followed by knife emojis were repeatedly posted in the comments to more than 50,000 viewers.

‘They defer, defer, defer’

When I talked to current NYCDM committee members about the doxxing, they readily acknowledged that their security protocols had been lax.

“The committee is coming back from that breach of trust and confidential information to do better in the future,” organizer Alice Siregar said. Among their changes: moving online planning from Slack to Discord, claiming the latter is more secure.

Over the last year and a half, the Dyke March has been quick to assume collective responsibility and acknowledge perpetrating harm, seesawing between apologizing to one side and then the other. But no one I spoke to on the committee mentioned any kind of direct amends or apology to the former member, who had been doxxed by one of their own.

“They defer, defer, defer,” said Walker, the Lesbian Avenger, of the committee. “‘We need to establish a process in which to undo the harm.’ Is that how you do it at home? What happens when you drop a glass on someone’s foot? ‘Alright, let me have a meeting about how to undo this.’”

Between the disrespect shown to Wolfe, and the backpedaling on empathy for Jews, several longtime Jewish participants in the march backed out. Walker skipped it, as did Shalev, who had quit the committee in December 2023, tired of feeling unwelcome.

Instead, Shalev organized an impromptu party called Shalom, Dykes, an alternative to the official march for Jewish dykes who felt ostracized by NYCDM. Nearly 300 people attended.

“I think it would have been very different,” said Zev — a Jewish former committee member who asked to be identified by their first name only out of concern for their safety — if the march’s organizers “were saying ‘People who support the bombing of Gaza are not welcome.’ You would have had a very different reaction than saying ‘no Zionists allowed.’”

‘What does it mean to call a Jew a white supremacist?’

When Kreines and the rest of the organizing committee reconvened from their off-season this year, they numbered only five people, instead of the typical 25 to 30. In late January, they issued a statement saying that the NYCDM wanted to get back to basics, “leaving behind the performative politics.”

This sentiment was a relief to the old guard. Walker and Wolfe considered getting involved again.

But, yet again, the non-hierarchical leadership structure and influence of social media interfered.

Commenters bombarded the post with accusations that the march was hiding Zionist sympathies behind a wishy-washy, apolitical public face.

“I’ve been actively in the committee for years but the active racism and Zionist apologist agenda forced me out!” one person wrote.

A group of around 15 former members, who had voluntarily left because they felt the NYCDM wasn’t sufficiently pro-Palestinian, strenuously lobbied the March to take an anti-Zionist position. When Kreines resisted, she was told by a former committee member in a meeting that perhaps NYCDM wasn’t the space for her anymore, and that the march “had moved past neutrality.”

On March 14, the Dyke March posted on Instagram that the aftermath of the 2024 march had left them with barely enough resources to perform basic functions, but they remained committed to anti-Zionist community standards.

The comments on that post, too, were full of rhetoric that deeply concerned Jewish dykes. “I remember seeing a comment from Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum, the rabbi of CBST” — Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, an LGBTQ+ synagogue in Manhattan — said Briana Aizin, who has attended past marches. “I know she’s a progressive Zionist and very pro-peace, and people in the comments were telling her she was a white supremacist. Not even thinking: ‘What does it mean to call a Jew a white supremacist?’”

Others were concerned by the committee’s apparent inability to resist social media pressure. The post had stated that “A number of dykes reached out to express their desire for the committee to take stronger stances on several issues, including an explicitly anti-Zionist position.”

“If enough people send DMs on Instagram expressing outrage, they will change course entirely,” Zev said. “When you’re dealing with the internet, there are always going to be people in your DMs, expressing outrage. If you don’t have actually thought-through systems on how to process that and not be derailed, you’re going to constantly be spinning in the wind.”

‘I don’t want to say the wrong thing’

The 2025 committee members I spoke with struggled to explain why the march was taking a stance on Zionism at all this year, when it was so clearly divisive. Siregar initially described that choice as a decision left over from the previous year that was out of their hands.

Siregar also said that Arab, Muslim and Palestinian dykes had expressed concerns that they would not be safe at the march unless it adopted an anti-Zionist stance.

“I do want to remind people that most Zionists are not Jewish,” they said. “It is oftentimes Christian nationalists who like to use that term for themselves, and they have a different working definition of Zionism.”

“I’m Jewish and I’m pro-Palestinian,” Nomie Keusch-Baker, a new member of the committee, said. “I feel like I have a place here,” they told me, but later expressed: “I don’t want to say the wrong thing.”

“We want this to be as safe a place as possible for everyone, that is the common goal,” Kreines said. “What you’ll find the difference is who each person is prioritizing as the most marginalized person, in terms of safety.”

I asked Kreines if she felt that Jewish safety had been deprioritized in exchange for Palestinian or Arab American safety. “I definitely think an exchange is occurring,” she said. “I don’t think I can specifically identify whose voices are being prioritized.”

No more ‘dyke drama’?

When the NYCDM was founded in June 1993 — after the first-ever U.S. dyke march, that April, as part of the March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation — its manifesto was clear. If you identified as a dyke, you were welcome.

Over the last year and a half, many Jewish dykes feel that openness has died.

“Queer communities intentionally are exclusionary,” Shalev said, because making a safe space for LGBTQ+ people inherently involves keeping some forces out. The problem with the Dyke March committee now, Shalev said, is that “they are thinking about Zionism as on the side of being unsafe in the community, in the same way they think about folks who are transphobic or racist. And so for them, it’s an integral value.”

The pain of that change feels very personal. Kreines told me she still feels guilt for allowing the committee to issue the March 14 statement committing to anti-Zionism.

Yet she is determined to make the Dyke March truly inclusive to all, she said, firmly believing that anti-Zionists and Zionists should be welcome. “I’m not giving up on the Dyke March,” she said. “Because if we’re all dykes, what does this matter?”

She’s not alone. Keusch-Baker, the new committee member planning to attend their first-ever march, told me in an email that they had founded a Jewish caucus and wanted to plan a Dyke Shabbat. They’re hopeful that the Dyke March can move away from debates about Zionism and get back to what it’s supposed to be about: celebrating dykes.

And practically, it’s likely that the vast majority of the tens of thousands of dykes who will assemble on Manhattan’s 5th Avenue this June will be entirely unaware of the “dyke drama.”

But others are moving on, feeling that the march was no longer a space for community connection. Shalev, who has an Israeli wife, is one of them. They continue to organize and plan events for Shalom Dykes, and recently circulated a letter with over 2,300 signatures of Jewish dykes who were dismayed by the march’s anti-Zionist stance.

I asked Walker, who has been organizing in queer spaces for over 30 years, if she was surprised by the toxicity that had taken over a queer group, like the Dyke March, founded in the name of safety and celebration. She laughed. “Dykes are a microcosm of the world,” she said. “All the contention you find in the world, you find in the dyke march.”