The Libreria Antiquaria Umberto Saba, was opened in Trieste in 1919. Photo by Giulio Bonivento

Trieste is a harbor city tucked into the northeastern corner of Italy, where hilly streets drop to piazzas along the Adriatic Sea. It’s where Winston Churchill marked one end of the Iron Curtain in his famous speech about the Cold War; where the Nazis placed Italy’s only concentration camp; where the Habsburg Empire ambitiously built up its only port before the empire collapsed in World War I; where Mussolini’s Fascism sank violent early roots.

It’s also where a bookshop on the Via San Nicolo has the one-time owner’s name painted above the door in bold, gold-colored letters: Libreria Antiquaria Umberto Saba. Saba, a Jewish poet and novelist, didn’t have a marquee name when he bought the bookstore in 1919, but he became one of Italy’s leading writers during the decades he ran it, and he immortalized it in a poem:

A curious antiquarian shop

is open on an obscure street in Trieste

Various golden hues of antique bindings

Delight the eye that wanders across its shelves

A poet lives serenely in this atmosphere

In this living memorial of the dead

He does his work…

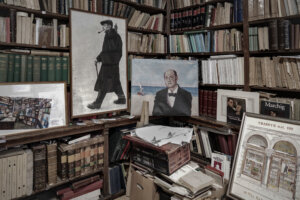

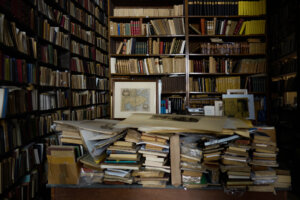

Near the end of 2023, it seemed like the 104-year-old bookstore that outlasted the poet was set to close. Wallpaper was peeling, wiring rusting, floor rotting. Shelves sagged beneath masses of dusty books. A long-time draw for literary tourists — who could study Saba’s books, desk, and a photograph of him striding through the city’s streets — was about to vanish.

But today, it’s more alive than ever.

On Jan. 28, the shop reopened. Buyers and browsers crowded it, sipping champagne. The fin-de-siecle, Vienna Succession design features have been restored and all the wiring and plumbing is up to date.

Even in Italy, where historical preservation is a habit, being able to tell so many stories about the past by telling the story of this store seems special.

A curious antiquarian shop is open on an obscure street in Trieste…

Saba was born Umberto Poli in 1883, to Felicita Rachele Cohen, who was Jewish, and a Catholic father named Ugo Poli, who converted to Judaism but abandoned the family before the boy was born. Umberto chose his pen name Saba to echo the name of a Slovenian Catholic nurse named Gioseffa (Peppe) Schobar. His mother gave him to her care for the first three years of his life. Some scholars believe he also took the name as a gesture to the Hebrew word for grandfather — saba.

Saba’s mother’s uncle was Samuel David Luzzatto, a renowned 19th Century Jewish scholar and poet born in Trieste. Saba wrote a piece of short fiction in which he appears. Still, he expressed more ambivalence about his Jewish side than the usual self-respecting Modernist. He wrote a poem about the “two races in ancient conflict” inside of him. He wrote a letter to a reader who wondered if he was antisemitic, saying he rejected all religious ritual.

Saba wrestled with his Jewish identity, but he was no stranger to Jewish feeling. In poems, he refers with seeming tenderness to a synagogue he passes on a walk, to the Jewish cemetery where he wanted to be buried — and is.

Various golden hues of antique bindings delight the eye that wanders across the shelves…

Saba was new to the book business when he leased the store from the Jewish community in 1919. World War I had just ended, Italy was in a nationalistic fervor that led to Mussolini’s rise. Saba had barely overcome a crisis in his marriage and a bout of the depression that would plague him the rest of his life. He and his wife, a Jewish woman named Carolina (Lina) Woelfler, had a young daughter, Linuccia.

Emily Dickinson once wrote that when a poem entered her mind, “a formal feeling comes.” In an essay Saba wrote about the bookstore, his notion of buying it feels like a poem being born, not a business.

“Walking through the Via San Nicolo one morning in 1919,” he wrote in “The Story of a Bookshop,” “I saw or noticed a gloomy cave for the first time and thought, ‘What a sad thing it would be to spend my life in there.’ It was although I couldn’t know it then, a premonition, because just a few days later I bought just that store.”

HIs plan was to, “throw all the old books in it into the Adriatic and to sell it empty at a higher price,” but he found he “didn’t have the heart to carry out the plan.”

He invested the remains of a small inheritance from an aunt, grew attached to the shop, and quickly learned how to find, buy and resell old — sometimes very old — books of literature, philosophy, history, religion, and books about boats. He ran his business on the ground floor of a six-story building built from the limestone quarried from a plateau just north of Trieste, one broken by ancient limestone gorges and underground caves. Saba may have had this in mind when he called his store a “gloomy cave.”

One enters it under a neoclassical stone arch. The poet’s name above the door has been repainted.

A poet lives serenely in this atmosphere…

Saba’s business doubled as a publishing house for friends’ writing and his own. In 1921, it issued the first edition of Il Canzoniere (In English, The Songbook), a collection of 600 poems that was republished by a major house in 1945, finally winning Saba his place as one of Italy’s leading poets.

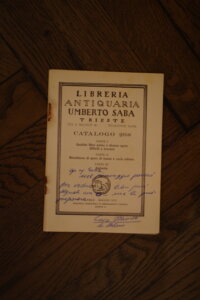

Other dealers taught Saba the importance of advertising his books with a regular catalogue with strong images, good writing and appealing typography. He worked to offer rarities that collectors could not find elsewhere. The shop, which resembled a fine art gallery more than any retail bookstore today, produced about 240 catalogues. According to la libreria del poeta, (The Poet’s Bookstore) a short but well-researched book by Elena Bizjak Vinci and Stelio Vinci, a husband-and-wife writing team, the book trade gave Saba “a certain economic security,” but it was precarious, and he didn’t get rich from it.

In 1924, Saba hired Carlo Cerne as a clerk in the store. Cerne, who was only 17 at the time, had been abandoned by his parents and was living in a boarding house for the poor. Cerne would later recall being hired as the turning point of his life. He became a prodigy of the skills an antiquarian bookseller needs — business ability, intelligence about people and literary curiosity.

They became known as a strong team in the trade.

Saba wrote brief stories about Cerne, and Cerne wrote a short essay about his life with Saba. Reading their warm but clear-eyed accounts, one gets glimpses of a complex relationship of mutual candor, teasing, frustration, trust and support that Cerne wrote was, “almost family-like.”

“I had the good fortune to find in him a second father and, what counted most for me, a Master,” Cerne wrote, going on to say that Saba “first taught me the profession and then taught me so many other things that in private life have served me so much.”

In this living memorial of the dead, he does his work…

Soon after Saba bought the shop, Mussolini entered and bought a book — the memoir of Luigi Settembrini, a 19th Century Italian political figure. Saba and Mussolini had crossed paths before the war. Saba wrote that he told the future dictator he believed that, “Italy’s guiding star would save us from his ideas.” His customer quickly left.

The 1920s saw Mussolini’s rise to power, and people living in buildings that flanked the city’s piazzas were woken at night by fighting between Fascist and anti-Fascist gangs.

Saba wrote a piece of short prose about changes in Trieste that revolted him, describing how young dogfight spectators, who had traditionally been “with the courageous little dog” now cheered on “a shepherd against a Scotch terrier — their shouts directed toward the large beast.”

“Europe’s youth would no longer feel any obligation to protect the weak,” he concluded.

He also bore witness to life under Fascism in more than 100 splintery fragments as short as one line, which he numbered and called Shortcuts. Saba ended up publishing, in an Italian newspaper, stabs of insight like: “Facts persist. We discover them in living them.” And: “Time is round. It comes back to itself.” And: “The 20th Century seems to have only one desire; to get to the 21st as quickly as possible.”

Mussolini expanded his claim to progress by issuing his racial laws, including bans against basic Jewish rights, in 1938. He announced them in a speech to a cheering crowd in Trieste’s main piazza. The city was also where refugees from across Europe managed to get a ship to Palestine. Saba visited Paris to explore the chance of finding refuge there, but got too homesick to stay.

The violent upheavals of Italy in the World War II era defy a quick retelling. Mussolini’s dictatorship gave way to his downfall in 1943, and the Nazis entered Saba’s city. Jews headed south for safety.

He turned the management of the store over to a gentile friend named Gregorio Bisia, a writer and bibliophile, who worked closely with Carlo Cerne to keep the store going — and fled for his life.

Saba and his family moved 11 times to stay ahead of the Nazis, being hidden by friends.

The Nazis set up their killing technology in the Risiera di San Sabba, a five-story brick compound in the area for husking rice. Most Risiera victims were Jews, Slavic gentiles and political prisoners, Paolo Volli — an attorney who sits on the Trieste Jewish community’s five-member governing council — told me. Most Jews seized in Trieste, he added, were deported to Auschwitz, Sobibor and other camps. About 1,200 survived the war.

In 1944, in Florence, as the Nazis retreated ahead of the advancing Allies, Saba wrote, “I Had,” a poem of outraged witness to losses that he’d suffered — an inventory of property, life, justice and basic moral confidence that he and countless others had lost. “I had a world,” he writes. “I had a little girl, today a woman. I saw the best of myself in her.”

“I had a beautiful city between the stony hills and the radiant sea… a little shop of rare and antique books.”

Each stanza ends with his finger pointing at both Italian and German Fascism, with a refrain that repeats like hammer blows: “Everything was taken from me by the vile Fascist and the gluttonous German.”

Facts persist — we discover them in living them.

Saba lived in Rome right after the war. He was ambivalent about returning to the city he loved but whose past and future troubled him. He was back in his bookshop in 1947, planning to write a history of the shop to publish in a catalogue, but he had difficulty — he’d lost faith in “the milk of human goodness” he drew on to write.

In 1953, he wrote Ernesto, a now-classic novel about the relationship between an older man and a teenage boy. Saba’s writing suggests he was bisexual, and Ernesto probably brought him more English-speaking readers than his poetry. Saba was not a Confessional or Beat poet, but readers of Jewish-American poets of the 20th Century will find a different but familiar home in his use of a self-revealing persona to express universal feelings.

Fighting depression, he increasingly left the store in Cerne’s hands, making him an equal partner in 1955.

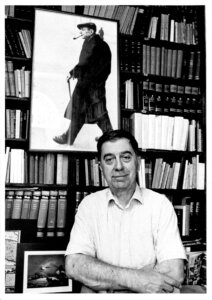

On Aug. 25, 1957, a year after his wife’s death, Saba died at a rest home near Trieste. In 1958, his daughter renounced her stake in the Saba store. Cerne became its sole owner. In 1967, his son Mario joined him, proving to be such a passionate bibliophile that father and son ran the business jointly until Carlo died in 1981; Mario took over, becoming a determined steward of Saba’s legacy for scholars and literary tourists.

In 2022, when Mario Cerne was 81, he told a visiting reporter: “I fear that this jewel may fall into oblivion.”

In 2023, he grew increasingly ill, closing the store for long stretches.

He died last January.

Time is round — it comes back to itself

Trieste’s Jewish community still owns the building where the bookshop is located. The journey toward the re-opening was started a year ago by the attorney Paolo Volli who works two floors above the Saba shop, in the same building.

“The bookstore was on the point of dying, and everything would be destroyed, and we had to do something to save a place that had a cultural, historical and touristic value,” Volli told me as he sat in the office where his father, Enzio, and his grandfather, Ugo Volli, avid book collector and Saba friend, also worked as lawyers.

A slender man with closely groomed white hair, he expressed his “strong feeling” for the shop, but insistently shared credit with others for making the restoration happen. “The council of the Jewish community approved this as a whole, and many people contributed to it,” he said.

In 2023, he began a fund-raising drive and drew in donors large and small, from a leading shipping company to a local café. He appealed to poetry lovers, general book lovers and citizens of Trieste who just wanted to be involved until he’d found the 120,000 Euros (about $125,000) that got the job done.

Dozens of people volunteered on behalf of their city’s literary legacy — after all, Trieste is where James Joyce lived for about 10 years, drawing from the city’s Jewish world as he wrote Ulysses. Joyce taught English to Italo Svevo, a Jewish-born Trieste writer (born Ettore Schmitz) whose novel, The Confessions of Zeno, made him famous. Svevo hung out with Saba at the store. Joyce lived above it before Saba bought it. Whether the two writers ever met is an open question.

As I made calls to Trieste, I kept finding multi-generational connections to a poet who died 67 years ago and often wrote about his disappointed yearning for company, for love.

Volli told me how Saba saved his grandfather’s book collection ahead of the Nazi occupation of Trieste, helping to secretly pass it through a side window at night, stashing the books along his shelves. His grandfather survived the war in Switzerland.

“I walked many times in front of this bookstore but it was really in bad condition,” Francesco Slocovich, president of the Kathleen Foreman Casali Charitable Foundation, a Trieste philanthropy, told me. “Our foundation, we were always thinking: ‘What can we do for renovating, for helping.’”

The foundation’s history goes back to the Stock Liquor Company and an executive named Alberto Casali and his wife. Lionello Stock, the company’s co-founder and a pillar of the Trieste business community, admired Saba’s poetry. In his bookstore essay, Saba recalled that Stock, whom he called, Nello, “loved the place and whiled away countless hours” in it.

“The goal was always to preserve the internal atmosphere of the shop,” said Aulo Guagnini, the Trieste architect who worked on upgrading Saba’s store and recreating its zig-zagging parquet floor and original wallpaper with a white and gold floral pattern. “That was done by strategically using track lighting to both illuminate the books but also to recreate the idea of the sort of dark cavern that Saba wrote about, when describing the store. The first step I took was to study the history of the place, and the history is what I follow.”

Pictures taken of the store before the restoration make it look like a cluttered ghost: Dusty light sweeps high shelves lined with uneven masses of books of all sizes. Looking at the photos feels like spelunking to the bottom of a lost cave.

The shop is also a large curiosity cabinet of Saba’s life. As workers emptied drawers and cleared shelves to ready it for its reopening in this century, they found photographs and artifacts from the last one.

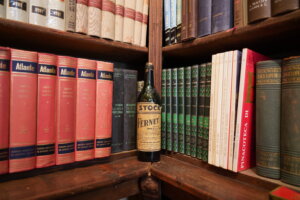

They found a bottle of Fernet, an aromatic Italian liquor, with a faded Stock label — allowing one to imagine the two men sipping and talking books. They found old photographs of Saba in what looks like middle age. They also cleaned a painting that had long been in the shop, a portrait of Carlo Cerne by Carlo Levi, the writer, painter and anti-Fascist famous for his novel, Christ Stopped at Eboli, about his exile to southern Italy for his politics. He and Saba were close.

The newly-reopened bookstore, which measures about 1,600 square feet, combines a museum honoring Saba with a retail business selling current books, and a space for readings and other book events. The rebuilt shelves of the museum section are packed with many of the old store’s 28,000 books — including 800 from Saba’s personal collection that were cleaned by dozens of book-loving volunteers from Trieste, a group that project leaders said was representative of the city’s multi-ethnic, multi-religious make-up.

The 20th Century seems to have only one desire — to get to the 21st as quickly as possible

The store re-opened on the one-year anniversary of Mario Cerne’s death, according to his daughter Ada. She has become the third Cerne to oversee the Saba bookstore. She lives in London where she works as the managing director of Edmund de Rothschild Assets Management, UK, limited, an investment fund associated with the Swiss branch of the Rothschild family.

Ada, 50, grew up visiting the store and said she could not imagine life without it. “I was used to walking in that street, and I know many people are used to walking there, and if they looked over and saw that the store wasn’t there anymore, I think it would be a terrible sense of loss,” she said.

“After my father died, it seemed crucial to move forward with (the project) because of the cultural and historical value it has for the citizens of Trieste. I had to do it,” she said. “We are a Catholic family, no issue about that, but the Jewish community is our partner in this initiative. This is typical of Trieste, which is a place of many different communities of religion, living side by side.”

She has worked with the project’s other organizers with constant thoughts of her father and grandfather, who died when she was six. She wasn’t the first Cerne woman to be supportive of the store. Decades earlier, her great-aunt Ada, for whom she is named, had loaned the poet money at a crucial moment for his business.

Ada attended an event last October at which Volli and the Jewish community returned the keys to the bookshop to the Cerne family, including Ada’s mother and daughter.

Ada said that the shop’s commercial element matters, but she takes a broader view.

“We will continue with this enterprise for everyone’s benefit, for everyone to enjoy,” she told me.

Ada was there at the opening with Massimo Battista, whom she picked to be the shop’s day-to-day manager. He owns another Trieste bookshop. It’s named Zeno in honor of the anti-hero of Italo Svevo’s novel. Battista plans a shop that will double again as a publisher of new work, one where writers can meet each other and their readers.

“I am 48 years old, and I belong to a younger generation, and I am a bookseller. I think they wanted someone who would bring a new way to think about the bookshop,” he said in an interview. “It is important that this is the place where Saba worked, but it will also be a place for literary events, where writers and readers can come together — a literary center.”

Dreamer of shipwrecks

If anything, Saba’s shop — returned to its understated elegance — looks almost too pristine. The finished shop reveals certain shapes of the original space with new clarity. In the soft glow of Guagnini’s lighting, one sees how one wall of books turns in a long curve.

It looks so much like the hull of a ship made of books that I wondered if Saba wasn’t looking at it when he wrote his Ulysses, a poem in which he sees himself in Homer’s hero as an old sea man, having lost a lot but not drowned:

O you so joyless and with forebodings

Of horror — Ulysses in decline — does no

Desire

muster tenderness in your soul

for a

pale dreamer of shipwrecks

who loves you?

Now, I thought, the dreamer could dream of a ship under full sail, the bookshop to which the people of Trieste have given new life.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO