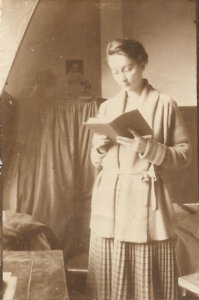

A portrait of Valland in her 20s. Courtesy of Camille Garapont Family Collection

I first met Michelle Young a dozen years ago inside the Woolworth Building — not just inside it, but deep inside it, past marble lobbies and hidden doorways most people never notice. She was overseeing one of her famous Untapped New York tours — part of the popular site she founded devoted to uncovering New York’s hidden history — making sure everything unfolded the way it should. Even from across the lobby, you could tell she had that rare kind of energy — someone genuinely excited by the world, and somehow makes you excited too.

From the minute she started pointing out lost passageways and tucked-away vaults, I knew we were going to be friends. She’s my kind of New Yorker: someone who thinks a secret staircase is cause for celebration.

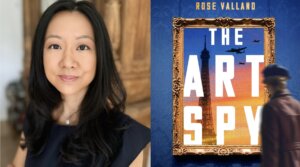

Michelle has always had a sixth sense for spotting the extraordinary hiding in plain sight. With her first narrative nonfiction book, The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland, she brings that gift to the page. It’s the breathtaking true story of Rose Valland — the quiet, relentless French art historian who risked everything to save Jewish-owned art from the Nazis.

The Art Spy isn’t just about paintings. It’s about defiance, survival, and the fragile, furious work of remembering. Michelle spent years lost in the archives, chasing secrets even the experts had overlooked, and what she uncovered isn’t just history; it’s a story that moves like a living thing: vivid, cinematic, and heartbreakingly urgent.

Recently, Michelle and I found ourselves in Los Angeles for AWP — the massive annual gathering of writers, publishers, and literary dreamers from around the country. After a long day of panels, we wandered into the red-boothed belly of HMS Bounty on Wilshire, a Los Angeles marvel marooned in time.

Built in 1924 as part of the old Gaylord Hotel, the Bounty once drew Golden Age actors, foreign dignitaries, and literary misfits. Over the years, it changed names — from The Gay Room to The Golden Anchor to, finally, HMS Bounty in 1962 — but it never lost its wood-paneled walls, brass ship fixtures, or flattering amber lighting. Cary Grant drank here. So did William Randolph Hearst. Winston Churchill even has a plaque over his favorite booth.

Outside, LED signs and fast fashion flash by. Inside, it’s all portholes, hushed booths, and maybe the ghost of a perfect dry Manhattan.Michelle ordered the petite filet mignon, and I went for the thick, round Baseball Steak — plus a Piña Colada, because, well, when in port.

The happy hour crowd was gloriously mixed: old-timers, punks, writers, and regulars. Time moves differently at the Bounty — a true holdout from an older Los Angeles, and exactly our kind of place.

We talked about how Michelle found Rose Valland, why her story matters more than ever, and what it feels like to finally finish the book you were meant to write. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity

Laurie Gwen Shapiro: Michelle, I remember when you first got obsessed with Rose Valland. But what year was that? How did you find her exactly?

Michelle Young: I discovered her in January 2021 while reading Göring’s Man in Paris: The Story of a Nazi Art Plunderer and His World by Jonathan Petropoulos. For years, I was reading almost exclusively narrative nonfiction books about WWII female spies — a robust subgenre! Every few chapters, this woman named Rose Valland popped up as the plucky nemesis to Hermann Göring’s Nazi art dealer in Paris. I couldn’t believe I hadn’t heard of her. When I realized there was no narrative nonfiction book solely about her, I thought: this is my story.

You’ve always been a detective at heart — building Untapped New York around uncovering hidden history. But this book took you into the archives in a whole new way. What was the most thrilling or surreal discovery you made?

One of the earliest was an unpublished chapter of Rose’s memoir, detailing her escape from Paris the day the Nazis invaded. It was hidden inside an unpublished biography sitting uninventoried in a museum in France. But the most thrilling discovery? Handwritten notarized testimonies from guards at the Jeu de Paume museum who witnessed the Nazis burning hundreds of modern paintings — including works by Picasso, Dalí, Ernst, and Masson. Rose had long reported this event, but after the war, she was attacked for her account by the very Nazis who did the deed. These testimonies, forgotten in the archives, proved she had told the truth all along.

I’ve seen your career evolve — from running Untapped New York to writing for major publications to now publishing this book with HarperOne. Looking back, did you ever imagine this is where you’d end up?

Not at all! I started out working in fashion as a merchandiser. But I’ve always followed gut instinct when it comes to my career. Going to architecture school at Columbia changed how I work. I don’t really make long-term plans — I iterate and follow my passions. I really felt fated to tell Rose’s story.

Rose Valland was hiding in plain sight, working in a museum teeming with Nazis. What made her so good at that double life?

Rose had been living double lives for years. She was from a rural background but educated among the Paris elite, learning to move between worlds. And she was a lesbian — her partner Joyce Heer lived with her by the mid-1930s, something Rose had to hide. She already knew how to conceal parts of herself. She was the perfect undercover operative.

Your descriptions of Nazi-occupied Paris are so immersive. How did you get yourself into that world while writing?

I know Paris deeply — I lived there during graduate school and stayed even longer because I fell in love with a French guy who’s now my husband. I always physically visit the places I write about. I also scour old newspapers, diaries, photographs, videos — anything that can layer in the texture of the time. You might not realize how many sources underlie any given scene in the book, but every sentence was built with exhaustive research.

Many of the artworks Valland tracked were stolen from Jewish collectors. How did that part of the story resonate with you?

Stories of looted art are about more than objects. They’re about families, war, persecution, and survival. When I’ve reported on art restitution cases, I’ve met the heirs — heard their struggles. It’s never about money. It’s about memory, dignity, and justice. That fight resonates very deeply with me.

You and I have talked a lot about how women like Valland get written out of history. Why do you think it took this long for her to get the spotlight she deserves?

Rose was blunt, stubborn, and didn’t come from the elite class. She was “difficult” by the standards of her time, especially in France. After the war, people wanted to move on — and she kept battling for art restitution until the day she died. She didn’t fit the mold of a palatable hero.

This isn’t just a story about art — it’s about bravery, resistance, and legacy. What do you hope readers take away from Rose Valland’s life?

I kept asking myself: “What would I have done?” Would I have risked my life under Nazi occupation? Would I have kept fighting even when I was gaslighted and threatened? Rose wasn’t a glamorous swashbuckler. She could have been me, or you, or anyone. Heroes are often ordinary people with skills that become crucial in a crisis.

Many of the artworks Rose helped save were created by Jewish artists Hitler considered “degenerate.” What does her story teach us about the power of art in shaping history and identity?

Art isn’t just decoration — it’s legacy. Totalitarian regimes know this. Art can be used to inspire or to exclude, to uplift or erase. Rose understood that protecting art wasn’t just about paintings — it was about preserving identity, culture and memory.

In today’s world, with rising antisemitism and cultural erasure still real threats, what does Rose Valland’s story teach us about allyship?

It’s simple: If there’s injustice, we fight it. Whether or not it’s happening to “our” group. History repeats itself, and allyship is essential. Rose wasn’t Jewish, but she risked her life every day for Jewish families she didn’t even know. That’s what true solidarity looks like.

Be honest — were you mentally casting the movie version of The Art Spy while you were writing?

Of course! Most people would think of Marion Cotillard, who would be amazing. But also Audrey Tautou, who could capture Rose’s nerdy side. Natalie Portman would be incredible too — Natalie, if you’re reading this, call me! I even daydreamed about who would score the movie — Nicholas Britell, the genius behind Succession and Moonlight.

If Valland were alive today, where do you think she’d be undercover?

Maybe still collecting information quietly — like the archival and librarian spies of WWII, gathering documents and news from abroad. Even in the digital age, real knowledge often comes from showing up in person, getting the context no algorithm can find.

Past portrayals, like The Monuments Men, softened or erased huge parts of Valland’s story — including her relationship with Joyce Heer. How did your research uncover the fuller truth?

Earlier writers didn’t have access to the personal letters, postcards, and papers I was given access to and tracked down. And they lived in a time when queerness was erased from public narratives. I was lucky to be able to research Rose’s personal effects and to speak with Joyce’s and Rose’s family. For the first time, we can hear Rose’s voice about what she felt, who she loved, and what it cost her. She wasn’t just a footnote — she was a full, complex, unforgettable human being.

You’re on the other side of finishing The Art Spy. What’s next? Are you sticking with art history and espionage, or is there another hidden figure pulling you in?

I can’t share exactly what I’m working on yet, but I’m moving toward the near-contemporary period. I’m always drawn to stories about taking down Goliaths, whether it’s Nazis or something else. I’ll keep digging deep into archives and telling stories from new perspectives.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO