A page depicting a Torah lesson given by an ominous-looking rabbi. Courtesy of Abrams Comics

Jerusalem is arguably the most contentious city in the world, so any work discussing it, let alone one that explores its four millennia of history, is bound to be controversial. But the 256-page graphic novel The History of Jerusalem: An Illustrated Story of 4,000 Years seems to have only garnered acclaim. Which is odd, considering it’s not a serious history book. More than anything, it’s a long polemic against the Jewish and Israeli claim to Jerusalem. Or maybe that’s why it’s so popular.

Written by French historian Vincent Lemire and illustrated by Christophe Gaultier, the English version was published in the U.S. on May 20, 2025; the French edition has been around since October 2022, selling over a quarter million copies to date according to the publisher.

According to Comics Beat, it’s been a consistent bestseller — in the Top 10 comics and Top 50 books — thanks to a strong PR campaign that included large posters on the Paris metro and the book’s timeliness due to the Israel-Hamas war.

Full disclosure: The publisher had asked me to write a blurb for the English edition, as a pop culture historian who often writes about the intersection of comic books and Jewish culture. I had strong reservations, which I let them know, particularly about the final chapters. The book is engaging, but it’s highly selective in the history it includes. So I agreed to provide the following statement:

“If a picture is worth a thousand words, only a graphic novel can tell Jerusalem’s 4,000-year story in a way that’s illuminating and entertaining. The golden city high above the Judean Mountains, at the crossroads of Asia, Africa and Europe, has been the heart of the Jewish people since the dawn of civilization and a place that’s shaped and reshaped the world throughout history — a history that’s brought alive in this book.”

But then the author, Lemire, asked to take out the reference to Jews. His publicist relayed that my blurb wasn’t “neutral” and that he didn’t want the book to appear to “favor one side over the other.”

Meanwhile, the other blurb was by Rashid Khalidi, author of The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, in which he argues that Palestinians are the indigenous inhabitants of the land and Jews are European colonizers. He’s a BDS activist, blames Oct. 7 on “violent settler colonialism,” and was reportedly a spokesman for the PLO in the late 1970s to early 1980s, while it was still designated a terrorist organization. Regarding Jerusalem; he’s related to the former Ottoman mayor.

Even if you agree with him on everything, “neutral” he’s not.

I bowed out from writing the blurb, but the issues I had with the book kept bothering me. So I asked two colleagues to read it: Dr. Motti Golani, professor of Jewish studies and chair of the Haim Weizmann Institute for the study of Zionism and Israel at the University of Tel Aviv, who was arguably the foremost expert in his field — he died unexpectedly shortly after conducting this interview — and Dr. Rehav “Buni” Rubin, professor of historical geography at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and an expert on Jerusalem in the ancient period.

An ‘antisemitic aroma’

“Lemire is known for his anti-Israel opinions,” Rubin said. “You shouldn’t have many expectations of him.”

Still, a historian’s personal opinions are one thing, and their professional work another, even if illustrated. But Lemire’s bias is evident from the very opening of the book.

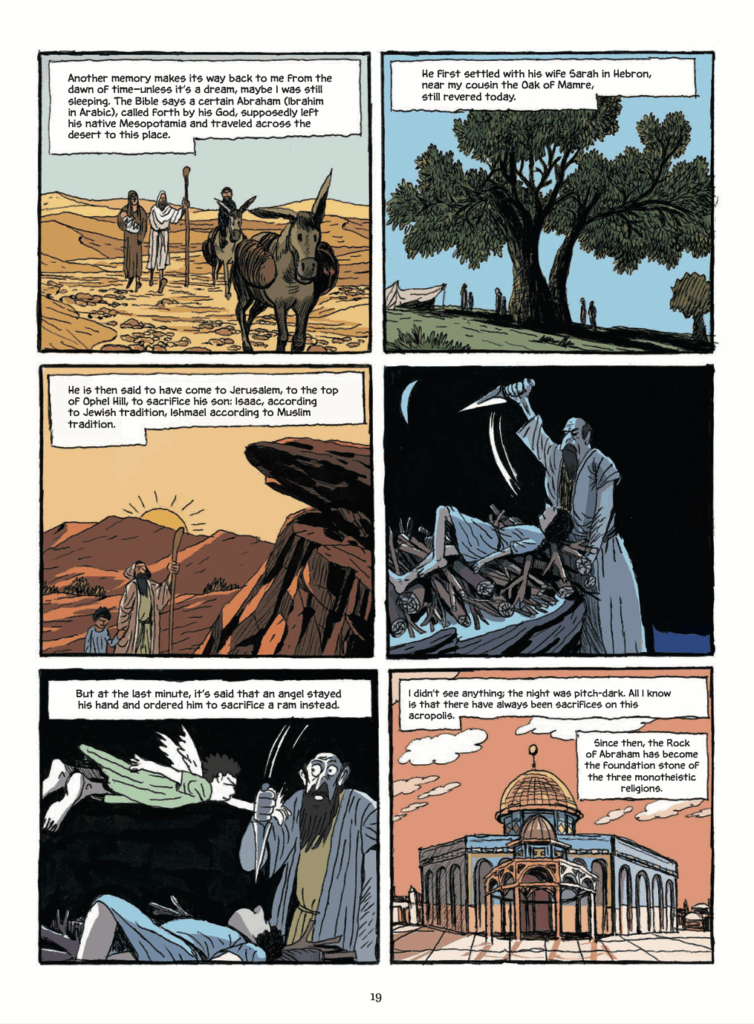

The narrator is a sentient 4,000-year-old olive tree, which introduces itself by two names: Olivia and Zeitoun, Arabic for olive — but not Zeit, olive in Hebrew.

The book’s historical facts are punctuated by the personal accounts of inhabitants and visitors to Jerusalem, most of whom are Arabs. There are relatively few Jews or Israelis who are allowed to speak. And when they do, they are often drawn in the black hat and coat of Haredi Jews.

“The denomination of Haredim, or ultra-Orthodox, is a fairly recent Jewish phenomenon. It’s about 150 to 180 years old,” Golani explained. “So to consistently show Jews as Haredim is stereotyping.”

“I also had the impression that, too many times, the Jews have a long nose,” he added about the drawings. “So there’s a choice made here, to show that this is how Jews look like, and that’s very glaring.”

Rubin calls the Haredi teacher giving a Torah lesson in the first chapter, for example, “in true tradition of antisemitic caricature. It’s the type of stuff the ADL used to deal with.”

Lemire and Gaultier also frequently depict Jews, and in later chapters Zionists and Israelis, as underhanded and subversive. In one scene, Jerusalem’s Chief Rabbi, Abraham Isaac Kook, is equated with Jerusalem’s Grand Mufti, Amin al-Husayni — never mentioning that al-Husayni was an ally of Hitler and a wanted war criminal — and it’s Kook who’s depicted as scheming to expand Jewish hegemony in the city.

“It’s part of this book’s antisemitic aroma,” Golani said. “After all, us Jews are known for our cunning.”

Conspicuous historical omissions

But the book’s faults run deeper than Der Stürmer-style cartooning. “Practically every page has some small factual error,” Rubin noted.

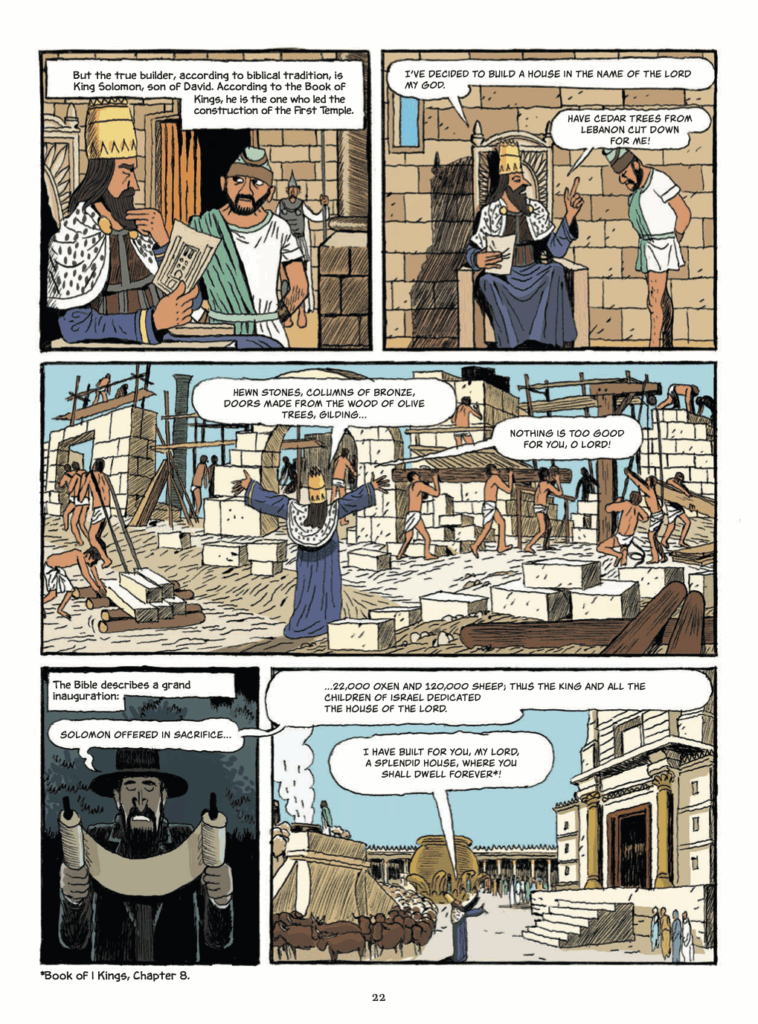

In one instance, King Herod is wearing an Egyptian crown. “That’s a great example of ‘Hollywoodism,’” he said. “The history doesn’t matter, as long as the crown looks ancient.” The section discussing King Solomon’s period, meanwhile, Rubin called “an unserious jumble.”

“It’s popular knowledge infected with stereotypes,” Golani agreed. “It’s Wikipedia knowledge.”

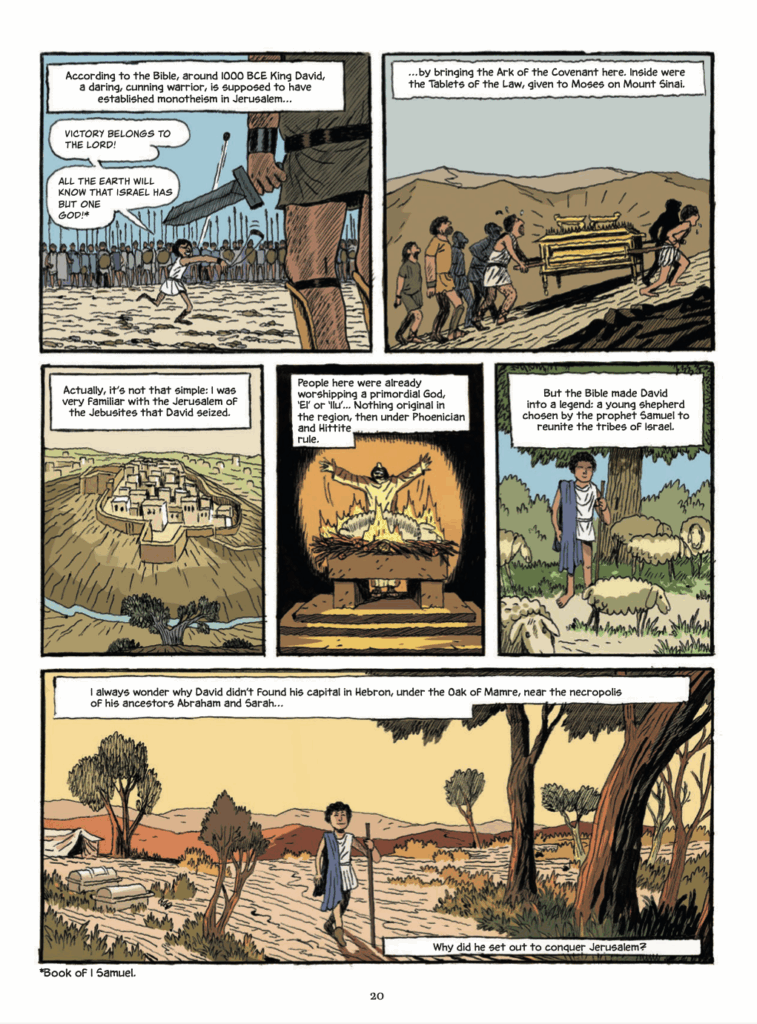

More egregious is that, “in a significant number of places, there is clear intent to minimize the ancient Israeli and later Judaic importance of residing in Jerusalem, and of the cultural and historic importance of Jerusalem for the Jewish people,” Rubin said.

Notably, the book misrepresents Zionism as solely a modern movement, born of the 19th century’s rise of nation-states. But from the time of King David, Rubin noted, “the term ‘Zion’ as a nickname for Jerusalem, and more broadly for the Land of Israel, has existed in Jewish tradition.” “Next year in Jerusalem,” for example, has been recited in the Passover Haggadah and other liturgy since at least the 11th century.

“Any attempt to cast doubt on the Jewish connection to Jerusalem is a type of propaganda. No serious historian can skip the Jewish phase of Jerusalem,” Golani told me.

“The Jewish connection to Jerusalem, even when there wasn’t continuous Jewish presence in Jerusalem, was inextricable,” Golani explained. “In the past few centuries and at least until the 1930s, the term Israel or Palestine wasn’t clearly defined and Jews largely referred to the land as ‘Zion,’” he continued. “That’s why the modern Jewish national movement is called Zionism. It’s very simple.”

Jewish religious tradition as a whole is similarly undermined. In the Torah lesson scene, the teacher says, “It is written in the Bible that an Egyptian prince of mysterious origins, named Moses, freed the Hebrew people.”

But Moses’ Biblical origins are anything but “mysterious”; he was born to Hebrew slaves, before being sent in a basket of bulrushes down the Nile. Rubin called the line “either complete ignorance or malicious intent.”

Later on, the narrating olive tree states that, “In exile, the Judeans invent Judaism: to preserve their identity.” According to this claim, the ancient kingdoms of Israel and Judah — where the term “Jew” comes from — or King Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, or a host of other events that predate the exile, have nothing to do with Judaism.

Most scholars place the complete edit of the Bible in the early Second Temple period, but, Rubin explained, different books of the Bible can be traced back much earlier, and oral tradition predates those by generations. “So the claim that the exiles of the First Temple didn’t have a tradition and they ‘invented’ it in the Babylonian exile is ahistorical,” he said.

And while the book undermines the Jewish history of Jerusalem, it paints a rosy picture of the city under Arab and especially Ottoman rule — implying that the Holy City and Holy Land would have enjoyed peaceful pluralism if not for the establishment of Israel.

“The fact is that for hundreds of years, the Muslims oppressed the Christians, Franciscan monks were imprisoned and Christian pilgrims had to pay special taxes,” Rubin said.

“Jews weren’t allowed to enter the Temple Mount or the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron,” Golani added. “They were allotted a narrow strip next to the Western Wall, not more than that.”

Jerusalem without Jews

But the book’s greatest fault, according to Golani, “isn’t just antisemitism. It’s the inability to admit that Jerusalem, as a symbol, is a Jewish creation. Nobody else’s.”

The Jewish relationship with the physical city, as opposed to the sacred symbol, is also denied. “They don’t note that Jews constituted a majority in Jerusalem very early on in the modern history of the city,” Golani pointed out, or that “it was the Zionists who brought about industry and education,” which “turned Jerusalem into a viable, significant city from just holy ruins.”

Several crucial events that shaped Jerusalem are conspicuously missing. The original idea to divide Jerusalem in 1937, for example, was a Zionist proposal, not British or Arab. The 1948 war that split the city is depicted as almost a turf war between local Jewish and Arab mobs, leaving out the six Arab armies and additional militias that invaded nascent Israel, as well as the Arab League’s promise of “a war of extermination. Also not mentioned is that, although the 1949 armistice agreement guaranteed freedom of access to the Western Wall, Jordan erected a landmine border. Or that in the 1967 war, Israel had no plans to seize east Jerusalem until Jordan attacked.

Perhaps the thing the book makes the greatest effort to ignore is that, for the past century, the Palestinian approach to Jerusalem and the land has been dictated by religion, often fervor, something Golani said did not drive the Jewish approach. “The Zionists didn’t get swept up in this mix of religion and nationality,” he said. (Though he added that, following the unification of Jerusalem in 1967, and especially in recent years, religion has played a growing role in Israeli policies.)

The book’s bias is evident not just in what’s omitted, but also, more insidiously, in how it depicts what’s included.

Yasser Arafat’s 1974 UN address is described fawningly as a “moving speech,” delivered by an Arafat drawn to look downtrodden. It’s not mentioned that he was the leader of a terrorist organization responsible for the murder of thousands of civilians.

Similarly, in the 1977 Camp David Accords, Anwar Sadat is drawn in round, soft lines, smiling. Menahem Begin, on the other hand, is depicted with sharp, harsh strokes, a scowling figure with a raised fist.

When the book draws to a close, it invites the reader to imagine a possible future in which Jerusalem becomes “A theocratic city where the devout have seized power” to “build the Third Temple and eradicate every trace of secular culture.” The art shows wraithlike figures with red eyes against a backdrop of smoke and fire. It’s a hellscape ascribed only to Jewish zealotry; apparently, there’s no other religious fundamentalism in Jerusalem.

“It’s not historical research. It’s not a historiography. It’s a narrative. It’s an attempt to create an identity for Jerusalem,” Golani said. “My deep sense of this book is that it’s not pro-Christian, it’s not pro-Muslim, it’s pro-Palestinian.”

“You can be pro-Palestinian,” he added, “but say so.”

“The trick of this book is that it mixes facts with bias, misrepresentation and opinion,” Rubin said, making it difficult to distinguish between fact and opinion.

The book ends with a call for Jerusalem to become “a capital city for two independent but allied states, a city shared but not divided, with Israeli institutions in the west, Palestinian organizations in the east” — presumably including the holy sites of all three religions— “and in the center of the city, a common municipality.”

However good or bad this might sound, as both Golani and Rubin pointed out, history books are meant to analyze past events, not advocate for future geopolitics.

Which points to the heart of the problem. The History of Jerusalem presents itself as a history book, by a historian. But it’s weaponized history, carefully curated to promote a viewpoint. Every word choice and brushstroke communicate its bias.

“People might see this as a history book. And it’s not.” Prof. Golani concluded. “It’s propaganda. It’s dangerous propaganda.”