Newly arrived South Africans wait to hear welcome statements from U.S. government officials in a hangar near Washington Dulles International Airport on May 12. Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

A South African who arrived in the United States this week under President Donald Trump’s plan to assist the country’s supposedly besieged whites has unexpected baggage: an apparent belief that Jews are “dangerous.”

Charl Kleinhaus was among the first of dozens of white South Africans to receive asylum under Trump’s new policy aimed at helping Afrikaners who say they’re victims of racial persecution..

Kleinhaus, a 46-year-old farmer, told reporters that threats to his life and land forced him to flee. “We just packed our bags and left,” he said. He arrived Monday with his daughter, son, and grandson, and is being resettled in Buffalo, New York.

A social media account that appears to match his identity tells a more complicated story than the one stamped on his immigration papers. It is filled with prayers for Israel and biblical affirmations — alongside posts accusing Jews of being “dangerous” and promoting conspiracy theories long recognized as antisemitic.

Now, as he begins a new life in the U.S., his resettlement is being aided under a decades old State Department protocol by groups including HIAS, the Jewish humanitarian agency founded to help Jews fleeing pogroms in Eastern Europe — and which now finds itself assisting someone who has reposted content from a Holocaust denier.

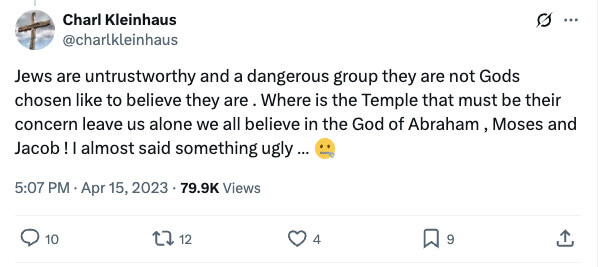

The Bulwark news site said it reached out to Kleinhaus on LinkedIn and confirmed that the X account belongs to him. A post from April 2023, which was deleted on Wednesday, reads: “Jews are untrustworthy and a dangerous group. They are not Gods chosen like to believe they are,” adding: “Leave us alone. We all believe in the God of Abraham, Moses and Jacob.”

The user reposted a graphic from July 2024 claiming that Jews believe Jesus performed “miracles by the power of the devil” and is now “in boiling excrement in Hell.”

He has reposted content from Stew Peters, a popular podcast host and Holocaust denier, in which Peters talked about “an Israeli funded media” and called Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy a “homesexual Jew that plays the piano with his penis.”

The same Peters video referenced the Rothschilds, a prominent Jewish banking family that is often invoked in antisemitic conspiracy theories, and also called the Israeli military “war criminals” and the country a “fake” one founded in 1948 and is “not the Israel of the Bible and these are not the Jews that Jesus was speaking of.”

And yet, amid those posts are others expressing fervent support for Israel, particularly after the Hamas attacks of Oct. 7, 2023. On Oct. 9 of that year, the user posted: “God will save Israel. He has always.” Weeks later: “Anyone who believes the Bible must back Israel 100%.”

God Will save Israel He Has Always pic.twitter.com/IqkGbod6YP

— Charl Kleinhaus (@charlkleinhaus) October 9, 2023

It’s a dissonance familiar to some Jews: a certain brand of Christian Zionism that can champion the state of Israel while harboring theological or racial suspicion toward Jews themselves.

HIAS did not comment on Kleinhaus specifically, but in a statement to the Forward on Wednesday, a spokesperson said: “HIAS remains steadfast in our mission to aid those fleeing persecution and seeking safety, regardless of their nationality, ethnicity, or background.” They added: “Our work is guided by the belief that every person deserves safety and an opportunity to rebuild their lives.”

A political contradiction?

In April, the Department of Homeland Security announced it would begin considering antisemitic social media activity as grounds to deny immigration benefits.

“Anyone who thinks they can come to America and hide behind the First Amendment to advocate for antisemitic violence and terrorism — think again,” said DHS spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin. “You are not welcome here.”

The posts associated with Kleinhaus would seem to fall within that scope — but it’s unclear whether they were ever reviewed. “The Department of Homeland Security vets all refugee applicants,” a senior DHS official told the Forward. “Any claims of misconduct are thoroughly investigated, and appropriate action will be taken as necessary. DHS does not comment on individual application status.”

HIAS may find itself in an awkward position. The group is a lead plaintiff in Pacito v. Trump, a legal challenge to the administration’s freeze on refugees who had been conditionally approved prior to Jan. 20. After the program was suspended in January, HIAS fought in court to restore it — and won. In April, a federal judge ordered the U.S. government to comply.

At the same time, the Episcopal Church — another longtime refugee resettlement partner — announced it would be withdrawing from the State Department refugee resettlement program entirely, citing a moral opposition to the prioritization of white Christian applicants over others.

President Trump has made fighting antisemitism a central thesis of his second term — but a new poll suggests many Jewish voters don’t see it that way.

According to the Jewish Voters Resource Center, 52% of Jewish voters believe Trump is antisemitic. Nearly half say his efforts to crack down on campus protests have worsened antisemitism. And 64% disapprove of how he’s handled the issue overall. The poll’s margin of error is 3.5 percentage points.

“It is very striking,” said Jim Gerstein, the pollster behind the survey, “that a lot of things that are being done in the name of combating antisemitism, Jews in America actually believe that these things increase antisemitism, instead of reduce antisemitism.” Gerstein polls for liberal and Democratic groups. JVRC, a new outfit, is chaired by Ron Klein, a former Democratic congressman who was until recently the lay leader of the Jewish Democratic Council of America.

Kleinhaus has not yet publicly addressed the online activity. He has spoken to both The New York Times and Reuters only of the threats he faced in South Africa and his gratitude for the opportunity to start over in the United States.

Whether his case slipped through a policy meant to keep antisemites out — or reflects the blurry boundaries of that policy in practice — remains to be seen.