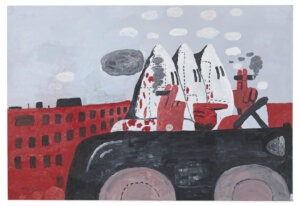

Trenton Doyle Hancock, “Schlep and Screw, Knowledge Rental Pawn Exchange Service,” 2017. Courtesy of Jewish Museum/courtesy of Collection of Hedy Fischer and Randy Shull

“Draw Them In, Paint them Out: Trenton Doyle Hancock Confronts Philip Guston,” a new exhibit at the Jewish Museum, juxtaposes work by two innovative American artists of different generations and backgrounds: Philip Guston (1913-1980), born Philip Goldstein in Montreal to working-class Jewish immigrants from present-day Ukraine, and Trenton Doyle Hancock, a Black artist who was born in 1974, grew up in Paris, Texas, and is now based in Houston.

The exhibit “is as much the story of one artist’s relationship to another as it is a broader dialogue about the role of art in the pursuit of social justice,” the exhibit’s wall text explains.

In the 1960s and 70s, Guston moved away from Abstract Expressionism towards figurative art, often painting a cartoonish image of a Klansman, who became a stand-in for himself. Many of Hancock’s works in this exhibit feature Hancock’s alter ego “Torpedoboy” interacting with Guston’s Klansman.

Only four years ago, in 2020 at the height of the George Floyd protests, the major retrospective “Philip Guston Now” was postponed by four major museums out of fear that Guston’s Klansmen would be misinterpreted as racist, even though such a reading is antithetical to the actual purpose of his work, which is to critique racism and antisemitism.

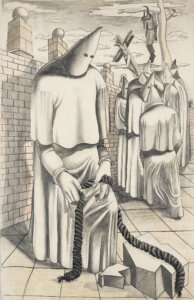

Guston was intrigued by how Nazis and their victims became numb to violence. “The only reason to be an artist is to bear witness,” he wrote in 1968. The dark humor in his paintings is meant not only to mock the KKK, but to make viewers consider their own complicity. “I perceive myself as being behind the hood,” Guston once said. “What would it be like to be evil? To plan, to plot.” On display are several paintings of Klansmen performing ordinary activities, such as “The Studio” (1969), in which a lone Klansman, a stand-in for Guston, paints a self-portrait while smoking a cigarette.

Hancock first learned about Guston when he was a 19-year-old art student. After he had created a black and white photo of himself wearing a white hood and a noose, “The Properties of the Hammer” (1993), his teacher asked if he was familiar with Guston’s work, and lent him a copy of a monograph on Guston.

“I fell in love with the forms, and how he used comedy to take the wind out of the sails of the KKK. He helped me understand where I could take my character Loid, and how I could embody that character,” Hancock says in the exhibition catalogue.

Guston’s work became a lifelong source of inspiration for Hancock; the two artists share a visual language, using cartoon-like imagery to critique white supremacy and racism. In addition to the Klansman figure, Hancock also depicts Torpedoboy, the superhero alter ego he created when he was 10. He later constructed a comics-inspired world called the Moundverse, populated by a figure named Loid, the ghost of a 1950s black sharecropper who was hanged by the Klan for having a white girlfriend, evoking the tragedy of Emmett Till.

The idea of wearing masks, not only the hood of the Klansman, but masks of assimilation, is central to both Guston and Hancock’s work. Guston himself changed his name from “Goldstein” when he was newly married and didn’t publicly disclose the fact that he was Jewish until his last major retrospective in his lifetime, in 1980.

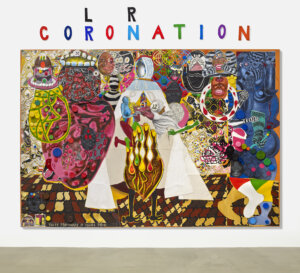

Hancock’s evocative early self-portrait, “The Properties of the Hammer” (1993), in which he wears a hood and a noose, and wields a hammer, which can build or destroy, is displayed across from Guston’s disturbing “Drawing for Conspirators“ (1930), made when Guston was only 17, showing an ominous Klansman preparing to lynch a Black man. This hooded lynched figure re-appears at the center of Hancock’s riotous Kodachrome creation, “Coloration Coronation” (2016).

In many paintings, Hancock depicts Guston’s Klansman making an offering to Torpedoboy. In “Step and Screw: The Star of Code Switching” (2020), the Klansman holds out a five pointed device to a white Torpedoboy, promising that the device will allow him to “live longer,” portraying code (or skin color) switching as a kind of superpower. In “Schlep and Screw, Knowledge Rental Pawn Exchange Service” (2017), the Klansman offers Torpedoboy an apple, with its Edenic promise of knowledge. Hancock incorporates bright plastic bottle caps into this painting and others, caps he has been collecting since he was a toddler, adding to the painting’s sense of bright, childlike delight.

Visitors can step into an inner room to view Hancock’s graphic memoir, “Epidemic! Presents: Step and Screw!” (2014), 30 black-and-white cartoon panels, in which Hancock’s Torpedoboy meets Guston’s Klansman. The memoir melds factual and sci-fi elements — Torpedoboy’s soul migrates to Hancock’s body, suggesting as the wall text says, that “racism and antisemitism are time-traveling, shapeshifting forces, rearing their heads in every era.”

As I neared the end of the exhibit, I noticed a man wearing a bright yellow shirt with a T in the center, and did a double-take. It was Trenton Doyle Hancock himself, quietly touring the exhibit before a lecture he was set to deliver; the T on his shirt stood for Torpedoboy.

Guston had acknowledged the limitations of art to achieve social justice, saying, “I have no illusions that I could ever influence anybody politically. That would be silly.” I wondered what Hancock would say about that, so I asked him — is achieving social justice a goal in creating his art?

“Quite selfishly I make the work for me — to equal something out that might be off balance a little bit, or just to document the things that I’m learning. It’s a very personal way to equalize myself,” he said. “There is a multitude of entry points and ways to view these things. But you know, I can say I aspire to a humanitarian world and hopefully empathy, and critical thinking, and I think, hopefully, it will work. I know that Guston’s work has been that for me, a way to look into what he was thinking, what he was dealing with, issues of the self, very personal things but also very public things, like how the world might be seeing him, his kind of maleness, his Americanness, his Jewishness, all these different kind of touch points that were about who he is coming out of these paintings, but then these are also great paintings.“

Hancock’s paintings also work on two such levels at once. Still, does he hope to make other people feel empathy through his art?

“I can’t say I even hope for that. Yes, I would love all the world to be a more empathetic place,” he said, then paused. “I’m not going to get that, not in my lifetime. I know art has changed me, and made me a more empathetic person, so there’s a fighting chance it can do that for someone else.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO