Photo by Michael Fein/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Judge Allison D. Burroughs on Monday pressed a Justice Department attorney to explain why the government’s effort to cut off billions of dollars in Harvard research funding would meaningfully address antisemitism on campus.

Burroughs, who noted her Jewish faith during the hearing, appeared skeptical of the Trump administration’s argument that the university had failed to protect Jewish students — and that the appropriate remedy was halting federal contracts, including those supporting medical research.

“Let’s assume for the sake of argument that Harvard has not covered itself in glory on the topic of antisemitism,” she said. She questioned how pulling funding for something like cancer research had anything to do with addressing antisemitism.

The moment was striking: A Jewish judge asking whether antisemitism was being used less as a shield for Jewish students and more as a political weapon. But it also carried echoes of Burroughs’ own family history — one shaped by flight from persecution and a commitment to justice forged across generations.

From pogroms to the federal bench

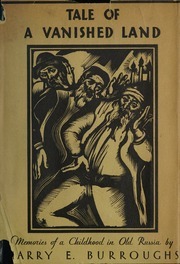

Judge Burroughs is the granddaughter of Harry Burroughs, a Russian-born Jew who escaped pogroms at the turn of the 20th century and became a Boston attorney and social reformer. According to his 1930 memoir, Tale of a Vanished Land, he was born Hersh Baraznik in 1890. He stowed away on a ship at age 14, landing in Portland, Maine speaking no English and with no money. He later made his way to Boston, where he sold newspapers on a Beacon Hill street corner in bitter winters.

Several times, he was found nearly frozen, saved only by the kindness of strangers, he wrote

Eventually, fellow newsboys nominated him for a Suffolk University scholarship. He Americanized his name and became a lawyer. But he never forgot where he came from.

In 1928, Harry founded the Burroughs Newsboys Foundation to support Boston’s underprivileged children and offered annual college scholarships. His book Boys in Men’s Shoes, originally published in 1944 and re-released this year with a new introduction, told of the work at the foundation.

In 1935, with the help of philanthropist Maximilian Agassiz, he launched a lakeside summer camp in Maine, called Agassiz Village, so low-income children could experience the outdoors — a nod to his own childhood memories in the village of Kashoffka. It now hosts about 500 campers each summer; next month, it plans to celebrate its 90th anniversary.

“He was a force of nature,” said Harry’s granddaughter, Cathy, who was born after he died. “A true rags to riches tale. Up from abject poverty he arrived from Russia penniless and helped support his family, adding that he was “a true humanitarian, he was a profoundly engaged philanthropist whose contributions endure into the present.”

‘Timid, undersized little man’

Harry described a seminal moment, witnessing a pogrom in Odessa. “I had assumed that massacres of Jews were incidents far back in history,” he wrote, “like the escape from the Egyptians and the burning of the temple of Solomon.”

But even before that, as a 10-year-old apprentice in Sevastopol, he encountered something that disillusioned him: the Czar.

Czar Nicholas II arrived in town with military fanfare. But Harry, peering through the crowd, was stunned by what he saw.

“The man whose name carried terror and authority to every corner of the land, for whom streets were carpeted with velvet and tens of thousands of his subjects prayed and sang, was a timid, undersized little man,” he wrote, adding, “I could not suppress a feeling of pity for him, a desire to cry.”

His defiance echoes now, as his granddaughter confronts a modern political strongman in her courtroom. President Trump has already denounced Judge Burroughs on social media, calling her a “TOTAL DISASTER” even before she rules.

The Trump administration says its actions are about protecting Jewish students on campus. But Harvard argues the government is weaponizing antisemitism to punish an elite university, a longtime target of the right, and doing so without due process.

Judge Burroughs seemed to agree, asking pointedly whether the government believed it could terminate contracts “even if the reason you’re giving is a violation of the Constitution.”

This is not her first time challenging executive overreach. In 2017, she temporarily halted President Trump’s executive order banning travelers from seven Muslim-majority countries, turning Boston’s Logan Airport into an early legal battleground over the policy. In 2020, Judge Burroughs presided over a case in which Harvard and MIT challenged the Trump administration’s plan to deport international students taking online classes during the pandemic — a policy ICE withdrew before she issued a ruling.

Echoes of history

Judge Burroughs’ father, Warren, was a Harvard graduate and World War II veteran. Her mother, Rima, remains active at Temple Israel in Boston, where generations of Burroughs family funerals have been held — including Harry’s in 1946, when he died at 56.

Harry never returned to Kashoffka. The pogroms, he wrote, were sanctioned by silence: armed hooligans encouraged by the state, while non-Jews went about their everyday business. Authorities often cracked down on Jewish self-defense groups, viewing them as politically dangerous.

Now, in a courtroom just a few miles from the Beacon Hill corner where Harry once sold newspapers, his granddaughter is weighing whether a different government’s use of Jewish suffering might be, in its own way, a misuse of power.

“I think the issue,” Judge Burroughs said near the end of Monday’s hearing, “is whether there’s a legitimate relationship between our distaste for discrimination and the approach the administration is taking.

Burroughs said she’d rule “as quickly as we can,” with Harvard seeking a decision before Sept. 3, when grant reporting deadlines kick in.