US troops of the 69th Infantry Division (left), shake hands with Russian troops on the wrecked bridge over the Elbe. Bernard Kirschenabum is second from left. Chaim Thau is in the center Photo by Allan Jackson/Getty Images

For the German town of Torgau, the 1945 meeting of American and Russian troops at the Elbe River at the end of World War II is a source of local pride. Every five years, they host a banquet for the veterans and their families and invite politicians to speak in celebration of Elbe Day. Pictures of the troops shaking hands hang in a nearby castle.

Jeff Thau, a retired Air Force colonel, has attended a number of the celebrations to honor his father, Chaim, a translator for the Russian Army who was in the Elbe photo. When Thau discovered another attendee was falsely claiming he was in the photo too, Thau quickly took it upon himself to set the historical records straight.

Through archival research, he discovered that the man the imposter was pretending to be was, in fact, Bernard Kirschenbaum — an American soldier, who like Jeff’s father, was Jewish. Both men also carried stories from the war that would stay with them for the rest of their lives.

This year, ahead of the 80th anniversary of the handshake, Jeff contacted Bernard’s daughter, Sara Kirshchenbaum, a freelance writer, and made note of their shared Jewish heritage. Sara now calls Jeff her “Handshake Brother.”

“Isn’t this such a powerful sign that the Jews are being attempted to be wiped from the face of the earth and then here, at this triumphant moment where Germany was cut in two by the Allies, that there were Jews on either side,” Sara said.

Chaim’s story

Chaim Thau was born in Poland in 1921 in the small shtetl of Zobolotiv, part of modern-day Ukraine. Growing up, he spoke Polish, Hebrew, Yiddish and German. After the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939, Nazi Germany and the USSR divided Poland amongst themselves. When the Soviets occupied Chaim’s town, Jeff told me, Chaim befriended the soldiers and learned Russian – a skill that would later save his life.

On June 22, 1941, the pact ended when Germany launched Operation Barbarossa and invaded the Soviet Union. Poland was captured and killing squads rounded up Jewish residents. Chaim took off into the woods near his village; he was the only one in his family of five to survive.

Jeff explained that Chaim spent 19 months in the woods, setting traps for animals, hiding in barns, digging shelters, and surviving off of handouts from kind farmers. After almost six months, Chaim met a childhood friend who had also escaped into the woods and they worked together to survive. They were able to steal a German soldier’s outfit and, using his German language skills, Chaim could go into town, pose as a soldier, and acquire food and medicine.

In 1943, Chaim and his friend encountered a group of Russian combatants, who mistook the two for German soldiers. However, Chaim was able to explain his situation to them in Russian.

As the Russian army advanced through Poland and Germany, they would pick up partisans and conscripts who spoke different languages, primarily Russian, German, or Polish. Since Chaim was a polyglot, they conscripted him into being their translator.

“My dad was thrilled,” Jeff said. “He’s got not just food and not just shoes and boots and clothing, but he’s got the comradeship.”

Chaim’s skills eventually landed him in the role of commander of an anti-tank battery, the very one that would arrive in Elbe the same day as the American troops.

Bernard’s story

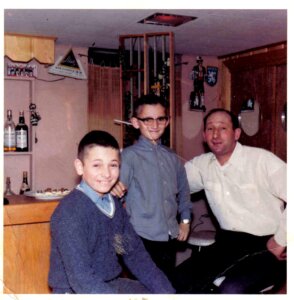

Bernard Kirschnebaum was born in New York City and was studying botany at Cornell when he was conscripted in 1943. For many years, the details of his military service were obscure to his family.

“My father was really traumatized by the war and he struggled emotionally his whole life with what he had seen,” Sara explained. “So it wasn’t something we talked about.”

While organizing her father’s home office in 2006, Sara Kirschenbaum found a photo of a dead child. She immediately showed it to her parents.

This opened up conversations about her father’s experiences in World War II, including the time he happened upon an arena of dead bodies in Leipzig, where he found the little girl.

His unit liberated the Leipzig-Thekla concentration camp hours after the Abtanudorff massacre. The Nazis had taken most of the camp’s prisoners on a “death march,” where they would walk the prisoners across Saxony in harsh conditions to prevent them from being found by the Allies. Those too sick or feeble to go were rounded into a barn which was then set on fire. Many who managed to escape were shot or killed by the electric fence surrounding the camp. Only 67 of the 304 ill prisoners survived.

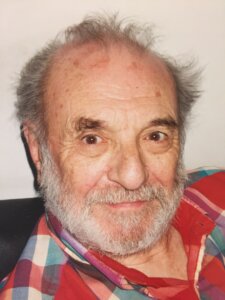

Although Kirschenbaum rarely spoke about the horrors he saw, he held onto the photo of the little girl from Leipzig until his death in 2016 to remember the victims he came across.

Elbe Day

On April 25, 1945, American and Russian troops met at the Elbe River in Germany. The next day, Allan Jackson, a correspondent with the International News Service embedded with the American army, wanted to pose the soldiers for a photo. But he couldn’t communicate with the Red Army, so he recruited their translator, Chaim Thau, to help instruct the soldiers how to stand.

There are two photos of the famous handshake. In the one more widely circulated, Thau is barely visible, his right leg sticking out behind one of the Russian soldiers. But in the second photo, taken just as the soldiers are starting to reach out to each other, Thau takes center stage, staring straight at the camera. To his right, with a cigarette in his mouth, is Bernard Kirschenbaum, his arm outstretched to greet his Russian ally.

Life After the War

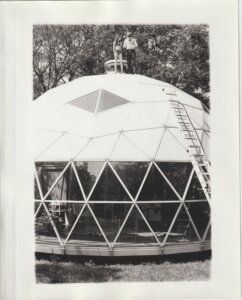

After the war, supported by GI Bill funding, Kirschenbaum studied at the Institute of Design in Chicago. Though he had a particular interest in the Bauhaus architectural movement, he also specialized in geodesic architecture. Duringthe Cold War, he was contracted by the Department of Defense to design 31 domes for the Distant Early Warning Line Station, built to detect a possible Soviet missile attack over the Arctic Circle.

“I think he really was trying to bring beauty and goodness to the world,” Sara said. “I think he was trying to help all people.”

He met his wife, Jewish artist Susan Weiler, after she contracted him to build a geodesic dome art studio in Stony Creek, Connecticut. They settled down together in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

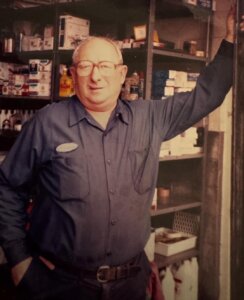

Chaim went to a displaced persons camp in Salzburg, Austria, where he met a group of refugees planning to join the Jewish Brigade and smuggle Jews into British Occupied Palestine. He became a member of the Brigade and fought in the 1948 war that established the state of Israel. After spending a couple of years in Israel, a Jewish immigration agency sponsored him to move to Wisconsin, where he took up work as a mechanic. His mastery of languages continued to serve him well, and made him a valuable friend to the slew of Eastern European immigrants who relocated to Milwaukee in the mid-20th century. He passed away in 1995.

Like Bernard, it took years before Chaim opened up to his children about his experiences during the war. In part, this was because of the trauma of his youth, but it was also due to his life motto: “Don’t look backwards; you’re gonna bump into something.”

For Jeff, this mantra is a testament to his dad’s resilience.

“If you look at what occurred, you got so many hurdles that would kill anybody else…so many hurdles that would freeze people in their tracks,” Jeff said. “But he kept on trying to make his way forward, to make progress and advanced.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO